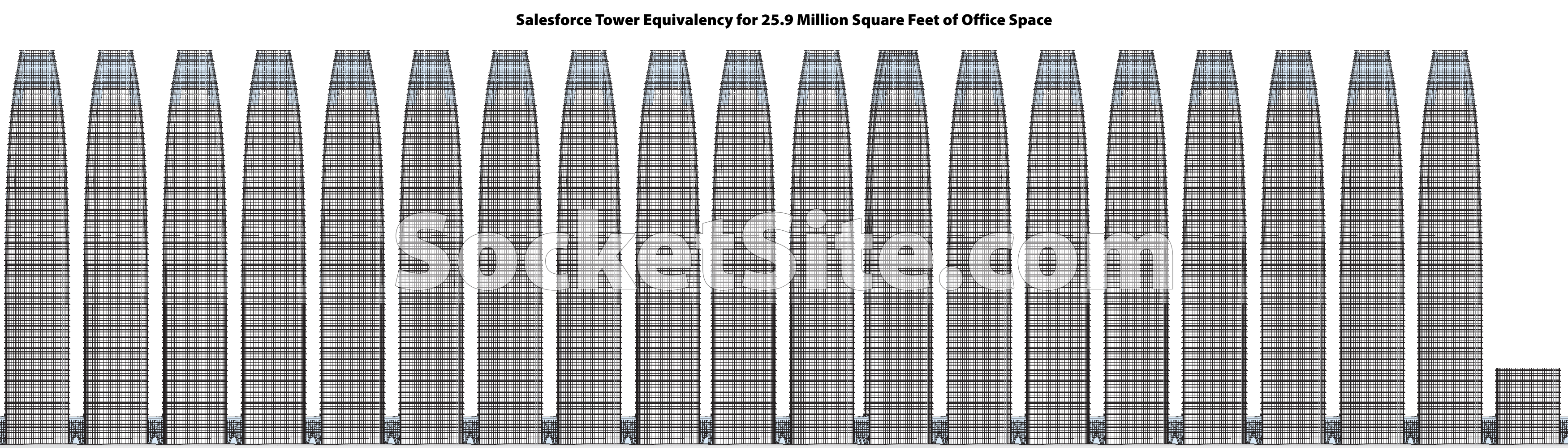

As we outlined last week, the amount of vacant office space in San Francisco has hit nearly 26 million square feet.

For context, the 1,070-foot-tall Salesforce/Transbay tower at First and Mission, which is the tallest building in San Francisco, contains 1.35 million square feet of office space spread across 59 floors.

And employing the framework we introduced back in 2020 and others have since co-opted as their own, there is now 19.2 Salesforce Towers, or over 1,100 Salesforce Tower floors, worth of empty office space spread across San Francisco, which is roughly enough space to accommodate between 148,000 AI or other full-time employees, based on an average, pre-Covid office density ratios, or up to 200,000 (a la Twitter/X or part-time) worker bees.

For additional context, that’s roughly 618 times Google’s headline lease of 42,000 square feet of additional office space in the city, which was billed as a bullish sign of a major player “bucking the trend” three years ago (when there was over 50 percent less vacant office space in San Francisco).

At the same time, there are now 7,400 fewer San Francisco residents with a job (557,600) than there were are the same time last year (565,000), with over 20,000 fewer employed people in San Francisco than there were at the end of 2019, prior to the pandemic, and over 14,000 fewer people in the local labor force (574,900), despite an unemployment rate of “just 3.0 percent.”

Vacancy rates will probably continue to go up for some time, but why didn’t you mention the recently signed 486k sq ft OpenAI lease? Goes against the narrative? This was publicly announced yesterday..

Um…wasn’t that space previously leased to quasi-legal, never profitable taxi hailing “platform” Uber, and so doesn’t really constitute a reduction in the amount of vacant office space? I don’t know, just asking.

Firms like CushWake break-out the data showing direct, sublease, and combined total. Sublease deals take longer to finalize because the tenant must get the landlord approval of subtenant. Not sure what date that sublease was finalized. It might have come in after they closed data for that reporting period. In any case, while it is large lease, it would only be small improvement with the magnitude of the overall vacancy rate. Other tenants are still giving up space. What is curious is that Open AI doesn’t have enough staff to occupy that chunk of space. Maybe they got great sublease rate and could afford to take some extra space to grow? Unicorns are known to take more space than they need because they aren’t spending their own money, which can get them into trouble later when the VCs get tired of funding their operating costs.

Thanks for the additional info. Agree that the amount of space being given up or placed on the sublease market swamps whatever space Open AI is taking up, or will take up in the near future.

Open AI is kinda the “it” company in the AI space for the moment, so if VCs get tired of funding their operating costs, they can just go public based on the strength of ChatGPT alone, not to mention their other projects. Word on the street is that they are in talks now to strike a deal involving employee shares that would boost its value to $80 billion.

What is curious is that Open AI doesn’t have enough staff to occupy that chunk of space. Maybe they got great sublease rate and could afford to take some extra space to grow?

Absotively! Proof, PROOF, PROOF that AI is going to explode like a toxic algae bloom and suck up all that empty space.. Now that‘s the “narrative” we wanna hear !

Hearing stories about how big employers like Google are really squeezing the “fully remote” segment of their employees, such as limiting their promotion opportunities. Y Combinator and other highly influential organizations are also pushing for more in-person as a philosophy. AI companies are signing leases. My guess is we’re getting close to peak vacancy. On the other hand, new construction office space is still coming online, such as in Mission Bay.

(3 years and 2 days ago):

Agreed. The recency bias here is strong. San Francisco was doom and gloom in 2001, 2002 was the “bottom” and by 2003 things were on the upswing. I see this situation potentially as being an even quicker turnaround as a vaccine could provide a near instant reversion back to normalcy.

…

I also think SF will rebound and be just fine. It will continue to be the tech capital, office space and rental space will be filled again. The “SF is cratering into a permanent death spiral” talk is overstated.

Keep the faith.

Yep. The SF Bay Area continues to dwarf all other metro areas in VC venture capital raised and there are still multiple trillion dollar companies near by. Young people – who are waiting longer to have kids or not having them at all – still want to be in dense, walkable cities with Mediterranean climates regardless of where their office is (or if they have one at all). The city definitely needs to get creative in finding ways to make residential projects pencil to quickly infill random parking lots with 5-over-1’s, and it needs its Guiliani Moment as well. But I’m not particularly worried overall. SF is playing with so much house money over the next 20 years it’s crazy. Government needs to get its act together or it could screw it up though.

Nobody wants to go back, even managers. The resurgence you are seeing is due to tax incentives. Hybrid/remote is the future.

This is just one anecdote, but I’d like to point back-to-downtown-office Panglosses to Upscale lounge meant to lure workers back into S.F. tech building closes:

The free lattes would be great, but most tech companies offer that. I don’t know that daily champagne would promote my personal productivity.

It may be that some companies intend to “squeeze fully remote employees”, but the question is, with many other employers embracing fully remote work, will the segment of the market that tries to go back to the office really move the needle enough to preserve the investments of office building owners? Forecast calls for pain.

Expensify how cute! And ironic given what they likely laid out for it: it’s quite plush (free pics are in the ‘Examiner’ for those not wanting to breach a paywall)

Clearly, tho, this company has very spoiled employees. Companies like Alphabet, Meta… you know the ones that have to turn to the dregs of Codedom for the kind of workers you can push around, don’t have this problem.

Uh huh. Don’t forget that when Google’s headline lease of 42k ft.² of additional office space in the city was announced three years ago (mentioned in the second to last ‘graph in the post above), that was before Alphabet cut 12,000 jobs in a mass layoff in January of this year. If in fact big employers like Google are really squeezing “fully remote” employees back into the office I don’t think it matters as much as the fact that there are just a lot fewer of them to squeeze.

Alphabet in its 10-Q filings earlier in the week outlined the costs of these efforts, including the costs associated with the reduction of office space (I personally hold Class A shares in this company). Amounts so far this year through Q3 included $649 million in “exit charges” to get out from leases and $207 million in “accelerated rent and accelerated depreciation.”

I don’t think the same linkage exists between unemployment rate and office vacancy rate nowadays. Its possible to have low unemployment rate and high office vacancy rate. Glad that I’m not office leasing agent in SF. Lost decade?

From 3:00 AM PDT on the same day as the above post, A New White House Plan to Create Affordable Housing: Convert Empty Office Buildings:

Go read the whole thing, it appears to be in front of Bloomberg’s paywall.

In the East Bay, BART already has work underway to convert some of their parking lots to support affordable, transit-oriented housing, and in the S. Bay VTA is doing the same thing with some of their light rail line parking lots, so it won’t take too much imagination to take advantage of the transit-oriented affordable housing programs. The take-up on the conversion of existing office buildings will be much more challenging.

And once again, “while it’s tempting to see, promote or editorialize an opportunity to convert all the vacant office space in San Francisco into housing, the conversion of existing office space to residential use still makes absolutely no economic sense for the vast majority of San Francisco buildings, due to the relative value of each use and the costs of conversion,” as we’ve outlined for over a year and others have finally started to figure out, even with the proposed financing incentives and subsidies that could be a boon for tertiary markets.

I am pretty sure that everyone who reads this site even casually is aware of that by now.

While there might not be an “opportunity to convert all the vacant office space in San Francisco into housing”, there exists some opportunities, plural, to get started by converting some existing class C office buildings into housing, and for those intrepid developers willing to do that work, this announcement might be interesting to them (as well as San Franciscans not in the real estate “game” who want to see more housing developed and are aware of the fiscal impact of endless empty office buildings).

What configurations do people have in mind when they suggest converting office to domestic space? I think of the floors of 50 Fremont, where I once worked, being divided up like New York style lofts ca 1985 (minus any residual charm): shoe boxes, with a short length of windows at one end, long sidewalls, and bathroom and kitchen at the other close to entry and elevator lobby. These long somewhat dreary units would ring each floor and have to sell at prices attractive to people with no other options. Probably better for management companies to mothball the portions of each building which can’t presently be rented and wait for “better times,” whatever form that might take.

They have in mind starting with the right kind of building: don’t start with a circa 1980’s 100’*200′ floor plate; think something like the Shell, Mills Tower or (even) the Russ Building: circa 1930 buildings with 75 foot towers (or at least a 75′ wall-to-wall dimension in some direction) Before WW II 28′ was the normative depth around the circulation core, so probably any building in that age group.

Of course this probably isn’t more that a fraction 10%? …20%? of all the vacant space, so that raises the point of what will happen when – well, if – all that space were to be converted, then what?

Not that we’re in any great danger of that happening, between Pollyanna, on the top of the page, and the Conversion Scold, at the bottom.

Here’s a few example office space to housing conversion projects that have already happened; none of the following were “recent” (if you define that term in ways that millennials would understand):

100 Van Ness (commonly considered the Ur example around here).

74 New Montgomery.

The Royal Insurance Building at 201 Sansome St..

While I am pointing out these examples, I am not saying, promoting or editorializing that this means all, or even the vast majority, of the vacant office space in San Francisco can be converted into housing.

And once again, As we first outlined over a year ago and have had to mention more than a few times since, the cost basis of 100 Van Ness was under $200 per existing square foot, including the adjacent building at 150 Van Ness which was then demolished to yield a “bonus” 429 units of housing. That’s why it was successful, an outlier, based on current building values, and actually made (economic) sense.

With respect to JamesSF’s notion of “mothballing portions of each building which can’t presently be rented and waiting for better times”, that’s essentially what happened with 140 New Montgomery (all of the following is taken from its wikipedia page). The owners of the building filed plans to convert the tower into 118 condominiums. However, those plans were put on hold during the 2008 financial crisis, and the building sat empty for nearly six years.

Following a surge in office demand in 2010–2011 (and presumably after the owners got bored with all of that carry forward tax loss harvesting), they changed the plans back to office space. Major renovation work began in early 2012, to improve the building’s seismic performance, install all–new mechanical, electric, plumbing and fire sprinkler systems, and preserve and restore the building’s historic lobby, at an estimated cost of US$80–100 million. In 2012, Yelp announced it had signed a lease on the building’s 100,000 square feet (9,300 m2) of office space through 2020.

In April 2016 a Boston–based REIT acquired 140 New Montgomery and according to property records, paid US$284 million for the property, at around US$962 per square foot. You know what happened next, right?

In 2021, Yelp did not renew its 2011 lease, and instead subleased a smaller space in a nearby building, due to the rise of remote work in the COVID-19 pandemic. As of May 2023, the building had a vacancy rate of 32.9%.

This would make a wonderful business-school case study, if an enterprising scholar could get Stockbridge Capital Group, Wilson Meany Sullivan and Pembroke Real Estate Inc. to give up their relevant financial records. I strongly suspect that the office space rents collected during the past fifteen years didn’t exceed the expenses of holding/maintaining the building when it was vacant (including presently), the renovation work in 2012 and the opportunity costs of foregoing selling the condos, which would have come to market during the recovery of residential following the financial crisis. But of course, once an owner refinances/rolls over a commercial mortgage or sells, that all gets papered over.

And this time, office space demand isn’t going to bounce right back.

And this time, office space demand isn’t going to bounce right back

Now there you go (again) being ‘Gloomy Gus’ : didn’t you see the points made at the top o’ the page ?? Offices are back!! Cuz’ those all powerful companies are going to browbeat their lavshly compensated employees back into expensive digs, the same ones that all powerful employees forced – just forced! – them to develop in the first place. Now if all this seems a little inconsistent… tosh! it just shows how reality is flexible, and the

cityCity is fortunate that the rules always bend themselves so as to benefit it.I cited 50 Fremont as an example of the many 1970-80s building whose floor plates would result in gloomy tenement-like living units if converted from their originally intended usage (though I do remember some lawyers almost living in their offices). The buildings Brahma (incensed renter) refers to, 74 New Montgomery and 201 Samsome (Royal Insurance Company), are prewar buildings with floor plates and window exposures that make them fairly easy to convert to housing, as Notcom points out. Plus the “patina of time” works in their favor. The Montgomery St side Mills, though it seems to have lost its inner court and great John Wellborn Root details (the cast iron circular staircase) is another good candidate. 101 Van Ness had good bones – it actually looked better stripped to the skeleton halfway through the conversion process, a bit like a Mies Lake Shore or SOM building. Plus it’s in a great location, in proximity to the Conservatory of Music, the Opera House, Davies (with its strange big ear balconies), and Hayes Valley. In comparison, there would seem to be little draw to living in charmless 50 Fremont-era buildings in an area with few small-scaled nearby attractions (Sutter Station?) – only the ghosts of bookstores, galleries and favorite lunch spots.

Speaking of 50 Fremont and ghostowns: part of the rotating display in the ED Library @ Berkeley currently is devoted to plans for the Transbay Terminal . IIRC the projected usage was 50K/day initially rising to several times that within a few years. With AC Transit’s – the main user – transbay service still at skeletal levels – and perhaps to get even smaller as pressure mounts to justify it with BART so undercapacity – all I can say is how fortunate billions were spent on this “Grand Central (sic) Station of the West” (and how really fortunate for SF that only a portion of it was its own !)

For a future discussion perhaps: SPUR has recently published a somewhat optimistic overview of office to residential conversion in San Francisco. Their figures seem to depend on rollback of many regulations, including seismic upgrades, and involve the inclusion of subsidies. This holds even in their ideal Scenario C: “a scenario in which the most distressed office buildings, those with vacancy rates of 75% or higher, are no longer desirable to office tenants and in which residential rents are restored to pre-pandemic levels.”*

They note that one of the reasons 100 Van Ness was successful was that there was no seismic upgrade required (“a rarity for San Francisco buildings over 40 years old”), due to the removal of the concrete and punched window outer cladding and its replacement with a lighter and more flexible glass curtain wall.

* “If the residential conversion generates a higher residual land value per gross square foot (RLV/GSF), there is an incentive for a building owner to consider pursuing conversion. If the residential conversion decreases residual land value, no pathway to the conversion is realistic.”

https://www.spur.org/sites/default/files/2023-10/SPUR_From_Workspace_to_Homebase.pdf

Interesting, thanks! OTOH, I’m less impressed by the very first lines of text

The Report seems to take this as a given, and will refer to it over and over again, tho it never attempts to explain how a lack of housing is hindering recovery when it existed pre-Pandemic, and DTSF was doing just fine…or seemed to be anyway. And, as always is the case with SPUR, the underlying theme is that the

cityCity is the Divinely ordained center of the Universe, and all efforts, from neighborhood groups all the way up to the U.S. Government should further that ( the Federation, I’m sure, would be included if it existed).But enough editorializing: the methodology seems sound and begins to discuss some of the challenges. One, that both it and you mentioned, is seismic upgrading. This a a good example of an extra cost that doesn’t figure in such projects in other cities – certainly not NYC or Chicago, et. al, (but likely does in West Coast cities) – but what to do about it? The Report seems to infer it’s a reulatory issue – upgrading is required when usage changes – in short it’s just another example of Red Tape we need to do away with, but is that really the case ?? Would you buy a converted unit in a building that skipped the upgrading (Hey the 1925 UBC was good enough for Gramps , should be good enough for you!)

Notcom: the phrase “workforce housing” is S.F. planning shorthand for housing priced at a level that workers outside of the tech and finance sectors can afford, based on their wages. This eliminates trustafarians.

It isn’t the same thing as “affordable housing”, but a useful rule of thumb is housing priced at a level at least 20% below surrounding market-rate prices. I would challenge the idea that an adequate amount of such housing “existed pre-Pandemic”.

I’m not challenging how adequate the supply was, I’m challenging the assertion that a lack of it is hindering recovery: we have the same jobs, and the same people doing them, living in the same places (adequately or no) …more or less; what we don’t seem to have, is the need, or desire, to do them in DTSF.

Of course, to me at least, all of this is somewhat irrelevant: I don’t think the question is really “how can we get DTSF back to what it was?” it’s “what are you going to do with 26M gsf – and growing – of empty space?”