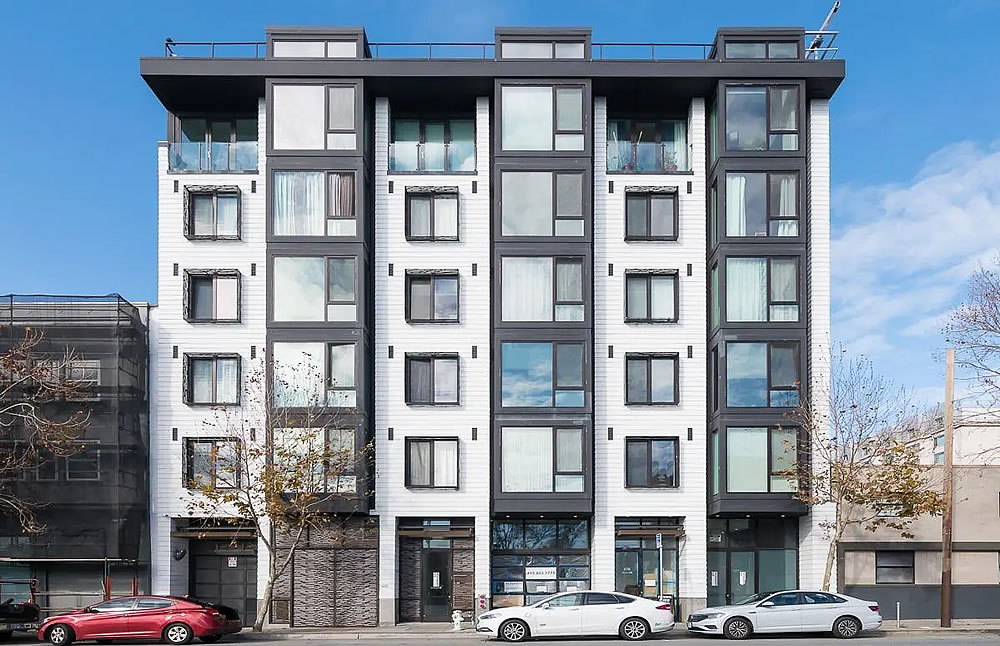

Purchased for $650,000 in March of 2016, the 545-square-foot, one-bedroom unit #206 at 870 Harrison Street, which was built by JS Sullivan in 2015 and features “floor-to-ceiling windows with an open layout creating a modern and open living space,” along with a Bertazzoni range in the kitchen and “abundant closet spaces throughout,” returned to the market priced at $699,000 in September of 2021, a sale at which would have represented total appreciation of 7.5 percent since the first quarter of 2016 or a little over 1 percent per year.

Reduced to $675,000 after a month on the market, the “well designed” unit was then listed anew for $675,000, reduced to $649,000, reduced to $639,000, and then relisted anew for $629,000 last July, after which the one-bedroom, which comes with a monthly HOA fee of $697, was delisted from the MLS and offered for rent at $2,899 per month.

Listed anew for $589,000 at the beginning of this year, a price which was reduced to $549,000 in February and then to $525,000 last month, the resale of 870 Harrison Street #206 has now closed escrow with a contract price of $515,000, which is officially “within 2 percent of asking!” according to all industry stats and aggregate reports.

At the same time, the resale of 870 Harrison Street #206 represented a 20.8 percent drop in value for the contemporary condo on an apples-to-apples basis while the frequently misreported index for “San Francisco” condo values is “still up 13 percent” over the same period of time, having dropped 17 percent over the past year.

And quite simply, that’s why new developments aren’t penciling, particularly for developers with high cost bases for their sites/land.

Exactly. New development in SF does not pencil. SF’s chief economic confirmed that recently and added that even without the inclusionary requirement it may not pencil. This at a time when SF is mandated by the state to add 82K units in the next 8 years. And this at a time when SF’s housing pipeline (around 75K) is significantly shrinking as projects are canceled. Related’s One Van Ness and the Chronicle residential tower at the 5M development to name two. Around 600 units between them.

As to the state mandate, even before SF’s post Covid woes, it never made sense. To reach that goal SF would have had to build at almost double the rate it had been doing during the pre Covid “boom” times.

You’re not presenting any new information here, simply regurgitating information from your other comments.

Even if new market construction doesn’t pencil at this point in the cycle, that doesn’t mean that the state (and San Francisco specifically) isn’t in a housing crisis. Housing is still unaffordable for many low and middle income families and individuals. The state is right to mandate housing production targets and housing review/approval reforms because the existing housing production system is fundamentally broken. The regulatory reforms happening now will hopefully pay dividends 3-5 years down the line.

There is no housing crisis; there has only ever been an affordable housing crisis. Building this type of condo did and does nothing to help provide affordable housing; it only exacerbates the problem. “Market rate” gentrification makes all housing more expensive, and crowds out affordable projects. Thankfully, few, if any, of these types of projects will proceed from here on out. Smart owners will take their 20.8% haircut now, before it becomes 30%. 40%, 50%…

This type of condo did nothing for pricing when it was new, but now that it’s not it sold for a lot less. That has always been part of the plan/hope. If there is a new version of basically the same condo the older one isn’t going to keep appreciating. That is what we see here. If building stops and there isn’t a better option they will rise back up

The unit didn’t sell for less because it was “used,” which is a tired red herring, it sold for less because demand has dropped and the market is depreciating. New construction values are dropping as well.

In addition, the construction of above-average priced housing raises the average price per square foot and cost of a neighborhood, by way of higher comps, compounded by gentrification (see: Rincon Hill, South Beach, the Transbay District, Mission Bay, etc.). That has always been part of the plan/hope.

But it is not a red herring. New places have fit and finish warranties, slightly older places have plumbing and electrical warranties, a little bit older and you still get the exterior finishes. Later its all on the owner. So there is a value to new and slightly “used” that becomes less valuable the more “used” it is.

That is of course not the only variable by a long shot but is one. Of course new construction coming down will also have a knock on effect. That is all good right, and the reason for building more. Bring prices down across the board.

“Bring prices down across the board.”

That might be how S&D works, ceteris paribus, on paper, but not how it works in the real world. Building lots of Ferraris does nothing to lower the cost of Hyundais, because they are aimed at completely different, not remotely fungible, market segments. If anything, the effect of a surfeit of luxury models is to drag up the asking price of lower-end models. And this is before considering that shelter is not a consumer good, but rather a durable asset that became an interest-rate sensitive gambling vehicle when the economy was turned into a financialized casino.

These “variables” are vastly more important than a building’s finishes, warranties, and infrastructure. The building is just a means to extract value from the land.

two beers,

I could not disagree more with everything you are saying here. What is Ferrari about this condo. Is it the flat base, or the modular cabinets, is it the light fixtures or the white ceramic tile? No, this place was a Hyundai when it was built. Overpaying for it because of scarcity, doesn’t make it a Ferrari. And then when you resell it, it’s a “used” Hyundai.

On resale the building isn’t a means to extract land value, that was already done. Now it’s just a place

I don’t think anyone, other than perhaps the “useful idiots” that call themselves “YIMBYs” in public comments segments during Planning Commission meetings, honestly ever believed that lots of market-rate construction would lower prices in the market overall. That’s just political rhetoric put out there by developers, flippers and other hangers-on in the real estate “game” who want other people to believe it so that there are more opportunities available for perpetuating gentrification and deriving profit from it.

During good times when interest rates are low, developers here mostly build new condos that are only affordable to a small segment of tech workers and top 1 percenters from outside The City and in many cases the country (e.g., the “Red Nobility” trying to squirrel away their wealth from the eyes of Chairman Xi Jinping). When interest rates rise, they stop building anything.

Now that new construction has ground to a halt, we will have real-world data in the coming years showing that local real estate markets do not work like the simplified Supply and Demand models discussed in college econ courses.

The problem is the cost to build affordable units in SF. This from the SFBT a few weeks back:

” Consider the math: The average cost to build an affordable housing unit in San Francisco is $1.2 million. The 46,000 affordable units alone will cost $55.2 billion over eight years. If inflation in construction materials and labor costs continues at the pace of the preceding eight years, we estimate the final figure will be closer to $75 billion.”.

Red tape can be cut and permitting expedited, but the labor and materials costs will continue to make building affordable (and now market rate) housing in SF problematic for years to come. One solution might be to use non-union labor but in progressive union-friendly SF that will not happen. Short of massive subsidies from government it’s unlikely there will be significant affordable housing construction in SF.

The affordability picture will improve as high paying jobs and more affluent people continue to leave SF which will drive significant price drops as the one featured here. SF just fell to 3rd place in the nation in terms of the cost to rent an apartment. As the “doom spiral” continues (a major financial district hotel is set to go into foreclosure) housing affordability will improve.

So what happens when bigger city like SF can no longer disguise the reality that it will never meet its housing target? Will Sac bully SF and threaten to withhold funds, like it does to the smaller towns? What impact would that have on the SF doom loop? Are progressive policies helping or hurting SF?

… not to mention a bad location (which will drop in price more and faster than better locations). If I were in the market for a *small* one bedroom, there are lots of other options besides staring at the backs of billboards, the K&L parking lot, and ever-jammed-up Highway 80. (And even if there’s decent soundproofing, the 2nd floor facing Harrison is not a great place to be, period.)

Starter? Starter? Someone would have to earn $160,000 a year minimum to afford that condo. The only industries in which that’s a “starting” salary is tech, and they’re maybe 7 percent of the workforce and shedding workers rapidly. And if you earned $160,00 a year, would you live in that cheap little box in that neighborhood?

One does not need to earn $160,000 a year to afford that condo.

Evidence: I bought my first property for that much while earning less than $160,000 a year.

That’s nice. The monthly mortgage on that purchase price is $4549. For that to be 1/3 of your gross income, you have to make $13,647 a month, or $163,374 a year.

Where is it written in stone that one’s monthly mortgage payment cannot be no one than 1/3 of one’s gross income?

It’s written in the code for the software that mortgage lenders use for evaluation of your application, for one. 30 percent is the federal standard for housing affordability. I’m sure you are aware of this.

It’s not that you cannot get a mortgage that requires more than 30% of monthly income to make your payment. You can. But you’ll be considered housing cost burdened and that status is going to have an impact on your loan terms or how many hoops you have to go through to get approved, or both. At above that mark, the lender is going to be more concerned about you affording other basic necessities such as food, transportation and health care costs.

No. You won’t be burdened by affording other basic necessities. Why? Because you earn $160,000/year. The rule makes sense for people who are living paycheck to paycheck by necessity, but at this income level, people only live paycheck to paycheck by choice (sushi dinners every night, wine clubs, new cars every 5 years, expensive vacations, etc.). Some people choose to spend their money on these items, others choose to spend it on real estate. But anyone at this level who struggles to put food on the table has only themselves to blame.

I have purchased several properties while spending more than 30% of my income on housing. No big deal.

also – first year lawyers (and, I think, accountants) earn that much.

first year … (and, I think, accountants)

🙂

Uhm, no. Unless you mean first year partners

To correct myself – first year associates at big law firms make >$200,000 (before bonus). Apparently accountants do make less, but still approaching $100,000.

I haven’t worked out the math, but I think it’s unlikely, in the real world, that your hypothetical first year associate at a “big law” firm would have the $100k down payment for this place (at its most recent sale price) sitting around in seasoned funds or qualify for a $410,000+ jumbo mortgage amount while still paying off their student loan debt from a top-20 law school.

You might object that you said nothing about student loan debt, or graduating from a top-20 law school, and that would be true. But both of those are pretty much implied for someone actually getting hired into the type of firms you mentioned, unless they were scions of a wealthy family. And if they had family wealth, then going to law school wasn’t necessary, and I’d question whether they’d really be shopping for a 545 ft.² one-bedroom condo in South Beach.