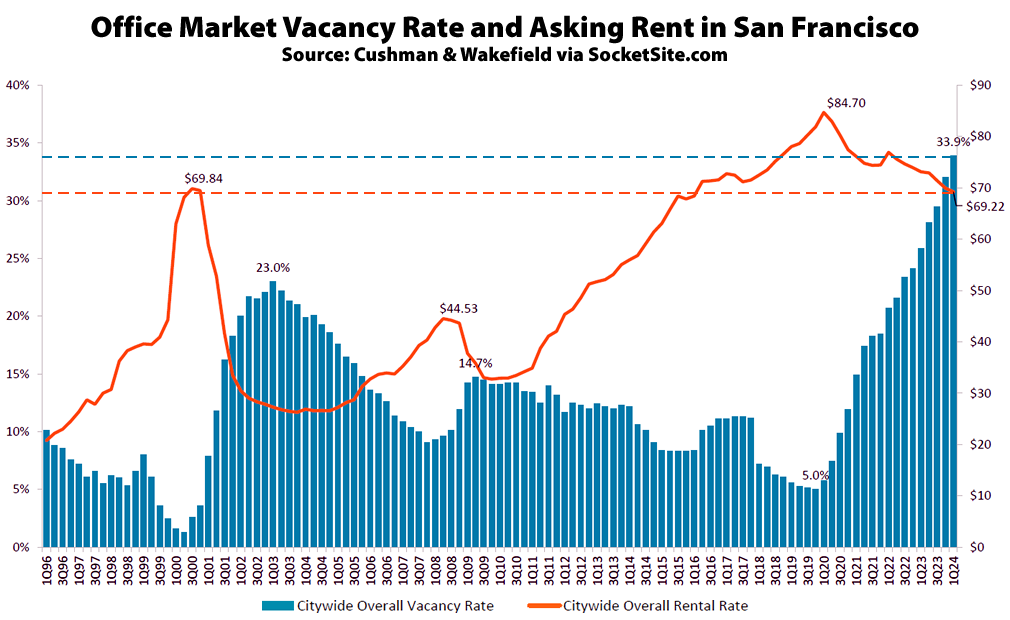

Continuing a trend that shouldn’t catch any plugged-in readers, other than the most obstinate, by surprise, the office vacancy rate in San Francisco ticked up to 33.9 percent at the end of last month, despite the over-hyped “AI Boom!” and other misanalysis in the local press.

As such, there is now over 29 million square feet of vacant office space spread across San Francisco, which is over a million more square feet of vacant space than at the end of 2023, with over 1.5 million square feet of negative net absorption in the first quarter of 2024, which is net of 843,000 square feet of newly leased space, representing 50 percent less leasing activity than in the fourth quarter of 2023, according to data from Cushman & Wakefield.

For context, there was less than 5 million square feet of vacant office space in San Francisco prior to the pandemic and the office vacancy rate in San Francisco has averaged closer to 12 percent over the long term, with a much smaller base of buildings and nearly 20 million square feet of space having been financed and developed since the dot-com boom/bust.

And while the estimated active demand for office space in San Francisco ticked up by around 15 percent over the past quarter to a total of 5.7 million square feet, which is 30 percent higher than at the same time last year, that’s compared to around 7 million square feet of active demand in the market prior to the pandemic, at which point there was over 80 percent less vacant space competing for tenants than today, and the total active demand is less than a fifth of the current available supply.

At the same time, while the average asking rent for office space in San Francisco inched down another percent over the past quarter to $69.22 per square foot, which is 18 percent below its 2020-era peak and the lowest average asking rent since the first quarter of 2016, it’s still over twice as high as it was at the depth of the Great Recession (at which point the office vacancy rate was under 15 percent) and over 60 percent higher than in 2003 (when the office vacancy rate hit 23 percent), with landlords’ still fighting, or obligated, to keep asking rents up.

And as we first outlined two years ago and others have finally started to figure out, “while it’s tempting to see, promote or editorialize an opportunity to convert all the vacant office space in San Francisco into housing, the conversion of existing office space to residential use still makes absolutely no economic sense for the vast majority of San Francisco buildings, due to the relative value of each use and the costs of conversion.” And yes, there are higher vacancy rate numbers still making the rounds, but it’s the consistency of the data set and context going back over a couple of decades, as our numbers do, that matters, with an escalation of poor reporting and cross analysis between data sets in the press and splattered across X.

I have a number of tech clients who foolishly renewed their leases after Covid when money was easier to get, who are now hanging on by their fingernails with no chance of getting any new investor money in. They are forced to survive on their revenue, which isn’t enough to pay for leased office space that is rarely used. If they make it to the end of their leases, they will not renew.

People don’t realize that a lot of tech companies provide services to other tech companies, like databases, development tools and communication tools. Every time a tech company lays off, they reduce the number of subscriptions they are purchasing from ten other tech companies, forcing those ten companies to lay off, so it just ripples down the line. 42,000 tech jobs have been lost since the start of this year (name link) with no sign of slowing. It’s no wonder that vacancies are continuing to increase.

I find it remarkable that rents in 2000 weren’t much different than they are now (or even much less than peak 5 years ago): talk about a bubble!

If I understand it correctly these are nominal figures, so you should use your imagination or tilt your head to make it look realistic.

Yes, it would be interesting to see the inflation-adjusted rental rate.

The office vacancy rate in early 2000 was around 1 percent, or roughly 34 times lower than today, and that was with nearly 20 million less square feet of space that has since been financed and built in San Francisco.

Correct (it was

34 times lessone 34th as much); but nevertheless the rents fell by more than half – what looks like ~two/thirds – in a little over a year and, more to the point, they didn’t return to that level, even in nominal terms, for a decade-and-a-half. That would seem to be bubblish…in the ‘Official Notcom Unabridged Dictionary’, anyway.If I did my math correctly, about 20.71 Salesforce towers?

Close. Over 21 Salesforce Towers Worth of Vacant Office Space in S.F.

I’d like to understand why prices fell much more sharply in earlier downturns when there was less vacancy than now. What is preventing building owners from dropping rents sharply enough that businesses forced out of SF or those with lower funds (nonprofits, public agencies) aren’t scooping up the empty space? Seems prices need to dip below $50/sq foot before we see much turnaround.

A big hint from above, “with landlords’ still fighting, or obligated, to keep asking rents up” and “nearly 20 million square feet of space having been financed and developed since the dot-com boom/bust.”

there’s a delay with owners playing extend and pretend – if they have to mark down rents the asset is worth less

so they just keep holding out for a reversal. their rate is probably locked in pretty low compared to the prevailing rate, so while some might have high enough vacancy they can’t service the loan, most can wait. i wonder if consolidation of ownership also plays a role in this – less competition.

Hunter, there’s a story from another city with high post-pandemic office vacancy which I think can help your understanding of why commercial rents don’t decline with the desired velocity to make the market clear (at least in the short-to-medium term).

In the Summer of 2023, the City of Los Angeles bid to lease 300,000 ft.² of space across 13 floors in The Gas Company Tower at 555 West Fifth St. to provide offices for The Los Angeles Housing Department’s staff. They thought they’d be able to negotiate a good deal on rent because in April of that year, following the owner’s default on $748 million in loans tied to that property as well as another tower, the building went into receivership. Prior to the start of negotiations for said lease, the value of the tower was estimated at about 57 percent of what it was valued at just two years earlier, and that was before accounting for the impending vacancy implied by the fact that the building’s second-largest tenant, law firm Sidley Austin, had already signed a relocation lease for another location nearby.

Question: The proposed L.A. Housing Dept. lease would have been a “win” for both the building owner, Brookfield Corp, generating unexpected, yet desperately needed revenue, and for The City, which presumably would have gotten a lease for an amount substantially less than they were spending in the building they were vacating. So why didn’t they agree on a “win win” deal that would make both parties better off?

Answer: The CMBS bondholders for debt tied to the Gas Company Tower Rejected L.A.’s Proposed Terms for the Lease. A previous time we talked about distressed office properties around here, Notcom was questioning if portfolio losses would get passed on to bond investors. My interpretation is that they clearly get a say, when the building is in receivership. Which of course raises another question: why would those bond holders vote against their own financial interests? Isn’t some (more) rent better than (a lot) less rent? There’s no way of knowing unless the bondholders willingly talk to a reporter. I am guessing they figured to make out on their CDS holdings a sufficient amount of time after the default.

thanks for these ideas, but none of them properly explain why rents dropped so fast in the sector during previous downturns and not this time. The market isn’t responding the way it used to: What changed that made building owners more likely to “pretend and extend” than ten years ago?

Maybe they learned from their mistakes?? The mistake being that prices are supposed to drop in downturns. It’s a common error for people who feel the best place to learn about the economy is an economics textbook…as opposed to a poly-sci one. But if they all stick together, and refuse to lower, will the world end, or will some kind of govt bailout be in the works? The country probably missed its Golden Opportunity for reform in ’08, by not letting the economy fall further, but its understandable why they didn’t.

Here’s a wild idea: according to the FTC (link at handle), increased concentration facilitates landlord collusion. The FTC post doesn’t mention price-fixing algorithm YieldStar, but it links to a ProPublica article that does.

The FTC uses the word, “conspiracy,” four times in the post. The FTC must be crackpots, because everyone knows there are no such things as conspiracies. Only kooks talk about white collar conspiracies. “Conspiracy” can only be applied to blue-collar crime, and not to white-collar crime, because billionaires, millionaires, professionals, and other educated people never collude, never would collude, and never even could collude.

My theory on why rents are dropping more slowly is because interest rates went UP not down, like before. An office building is like a bond, with rents equivalent to interest. When interest rates double, the value of the office drops in half if the rents stay the same. A building that is worth 20M when interest rates are 5% is generated 0.05 x 20 or 1M per year. If interest rates suddenly go up to 10%, that $1M per year is only worth 10M because 0.10 x 10 is $1M, which is what the building is generating.

Normally, interest rates would go up during boom times when rents would be doubling, but that didn’t happen. When the owner goes to refinance their $20M loan, no bank will give them that much for a building now worth $10M. To refinance that building, the owner will have to put money in. But now, it’s even worse. Not only have interest rates gone up, rents should be going down. So if rents drop by half, the building drops by half again. In the example above, rents are now 0.5 and so the building is worth $5M: 0.10 x $5M= 0.5M in new rents.

By not accepting the new rent, the bank won’t have to mark the building to market and might loan something closer to $10M instead of $5M. The bank does not want to mark the building to market because they know the owner will default, and neither does the owner, so they can both pretend the building is still worth something closer to $10M and not $5M and the bank will loan that amount with a wink and a nudge to keep from writing off the loss when the owner hands the bank the keys to a $5M building in exchange for a $20M mortgage that is coming due (most are 7-10 years). What the bank can’t do is loan $10M if the building is fully occupied and generating $0.5M in rents. The same way that a single tenant building’s value doesn’t drop to 0 when the tenant moves out and no one immediately follows, the bank has some wiggle room to value the building based on the old rent as long as it is not actually rented at the lower rent.

Of course, this is not a long term solution because the landlord can’t pay the mortgage with an empty building.

Agree with tipster, that’s my thoughts here too (and then some). In addition, to further illustrate the potential impact of higher interest rates: Assume the owner had cash on hand “to put money in” to cover the loss in the building’s value after renting at a lower rate. Chances are, they might be better off keeping the space empty and holding out, while investing the cash in the capital market, possibly at 0 tax after offsetting losses elsewhere.

Interesting thought! This makes logical sense to me, but it is also a disaster for our commercial building recovery, and likely means many more years of an empty downtown…

Maybe office building landlords refinanced during pre-pandemic period of lower interest rates this time around?

Pull out those pencils because the equations for office to residential conversion have changed: https://www.sf.gov/mayor-lurie-board-of-supervisors-reach-agreement-on-legislation-to-convert-empty-offices-into-new-housing

I read the entire press release twice. I found it underwhelming on the substance, but I have to admire Mayor Lurie’s PR staff’s chutzpah. The legislation won’t unless and until developers acquire a meaningful number of existing Class B and Class C buildings and actually convert them to residential use. Sure, this reduction in fees and requirements will probably contribute to conversion project viability at the margin, but doesn’t and isn’t going to produce new apartments out of vacant office space: private sector developers will have to do it unless some magic source of public funding appears from somewhere.

And S.F. has an uncommonly reticent and risk-averse pool of for-profit private sector developers.

I often agree with you, and always defer to your grasp of the nuts and bolts of RE, but even in the unlikely event that these types of conversions ever become feasible, where do you see the demand coming from for all these potential residential units? How are vacancy levels looking now at the “Hub,” NEMA, 50 Jones, and all the other condo or rental debacles along Market? Even if all SF jobs RTO five days a week, the types of jobs that would pay the rents or mortgages needed for such conversions are in decline. Sure, phenomenal proximity to public transportation (which even so seems to be in terminal decline), but even if street-level retail was magically filled to 100%, the FD makes for a dark, cold, parking-scarce, unappealing residential neighborhood.

I think even with government- and business-mandated RTO (in order to bail out property owners and banks!), we’ve been through a sea change. The truth might be that the bubble-induced maniacal rush to build!build!build! resulted in a historic misallocation of capital and socially-destructive repurposing of land that will take decades or generations to resolve.

Now, SF no longer has the the type of land that could host the types of jobs that can’t be outsourced or done remotely – it’s all offices and condos now! I wonder how many “Salesforce Towers” of vacant office space there are now, and how many we can expect in the years ahead?

While I don’t disagree with any of your observations, you’re essentially resting your case on a market rationalist analysis of the local housing market, and I’ve found that those playing the game don’t necessarily think about the local market in strict market rationalist ways.

To answer your first question: I don’t know what vacancy levels are at the rental apartment complexes in and around Market St. that you mentioned, but consider that in July of last year, asking rents in San Francisco were actually trending up, in spite of tens of thousands of people moving out of San Francisco since 2018 and accelerating since the start of the pandemic (I would be willing to bet that few of those leaving were real estate agents, developers, or other hangers-on in the S.F. real estate “game”).

You can go back four years ago, and we were having a recurring discussion around here about the fact that people didn’t have the high remuneration jobs that would pay the rents or mortgages needed for local housing. And yet, according to the Feb 6, 2025 article in The Examiner ():

So in the event conversions from office actually come to market, I think adequate demand will be there regardless of whether or not potential tenants have, on paper, on the resulting units. Because many such workers are being approved for apartments they can’t afford right now, and have been for quite some time.

Pull out those pencils because the city has recently removed the BMR requirement for office-to-residential conversions. Look for the article entitled “Mayor Lurie, Board of Supervisors Reach Agreement on Legislation to Convert Empty Offices Into New Housing” at sf.gov.

Because there’s enormous demand for market rate units in a dark and desolate neighborhood with no parking, in a city where the type of office jobs that might pay well enough to afford such market rate units are not-so-gradually disappearing, while inventory, days on market, and price reductions are all increasing?

Good luck!

Strava subleasing 3 floors, 41,000 SqFt, from Meta (FB). Beginning of new office leasing market for SF?

Probably won’t meaningfully decrease the amount of office space on the market. Google is pulling out of it’s lease at One Market Plaza this year.

Anyway, Related California are that will add no less than 350,000 ft.² of office space and 7,400 square feet of retail to The City’s inventory by 2030.

Keep in mind that before that future addition, at a time when over 37 percent of San Francisco’s office space is siting there vacant, San Francisco already has more than 10 million square feet of entitled, approved office space that could be built, but their sponsors are waiting for the market to recover.

Apparently, developers believe that S.F. doesn’t have enough office space. But the vacancy rate is rising.

According to an article bylined by Patrick Hoge in The Examiner () and updated a few days ago:

And just to add future fuel to the office supply fire, Lendlease, the developer behind the failed Hayes Point tower that has been an empty hole since 2023 is in the process of being granted an amendment to its previous approval which dispenses with the on-site affordable housing and increases the previous plan for office space on the second-floor by over 18,800 ft.²(for a total of 252,905 gross ft.²).

Keep in mind that, according to that June 2024 article in The S.F. Standard () Avison Young projected that under any scenario where leasing activity is less than that recorded during the early 2010s, The City’s office vacancy rates will not return to under double digits until 2033 and probably as far out as 2042. In short, S.F. is already oversupplied with office space and is likely to be so for the better part of the next decade (or two). Which is why developers need to get cracking on converting older office buildings to residential.