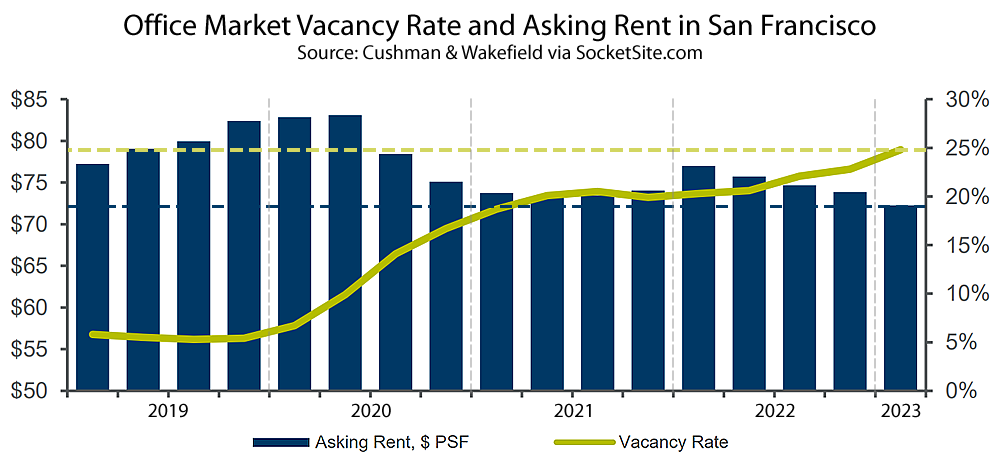

The effective office vacancy rate in San Francisco ticked up to just under 25 percent in the first quarter of this year, representing over 21 million square feet of vacant office space spread across the city, including 15.8 million square feet of un-leased and non-revenue producing space, which is up from 15.2 million square feet of non-revenue producing space at the end of last year, and 5.3 million square feet of space which is leased but unused and being offered for sublet, according to data from Cushman & Wakefield.

As a point of comparison, there was less than 5 million square feet of vacant office space in San Francisco prior to the pandemic and the office vacancy rate in San Francisco has averaged closer to 12 percent over the long term, with a much smaller base of buildings.

At the same time, while the estimated active demand for office space in San Francisco did increase by nearly 18 percent in the first quarter of this year to 4.5 million square feet, that’s compared to over 7 million square feet of active demand in the market prior to the pandemic, at which point there was a fourth as much vacant space as today.

With the continued increase in the vacancy rate, the overall average asking rent for office space in San Francisco dropped another 190 basis points over the past quarter to $72.26 per square foot, which is 4.5 percent lower than at the same time last year and around 13 percent below its 2020-era peak, despite landlords’ efforts to keep asking rents up and with a “large quantity” of commercial mortgage debt that’s slated to mature this year, which is poised to stress the office market even more and force some hands, with the cost of capital having jumped, for both owners and occupiers alike.

And as always, “while it’s tempting to see, promote or editorialize an opportunity to convert all the vacant office space in San Francisco into housing, the conversion of existing office space to residential use still makes absolutely no economic sense for the vast majority of San Francisco buildings, due to the relative value of each use and the costs of conversion,” as we’ve outlined for over a year and others have finally started to figure out.

the absurdity of the situation is the stickiness of rents at this high level. Rents have barely budged despite the reality of demand, cushioned by the gradual expiring of leases by companies that haven’t disappeared as in prior major shocks to office demand (see: dot com bust) when asking rent plummeted overnight and the office market was poised to start recovering sooner. Seems like rents will just continue to have the air taken out of it steadily and too-slowly over several more years before it actually represents a real equilibrium. The individual rational decisions of individual building owners does not add up to a rational situation overall. This is a perfect example of market inefficiency with regard to supply and demand.

it is completely bizarre to me that building owners won’t lower office rents to encourage other uses or expansion for local companies/non-profits that need office space. Feels like they are actively leading to a bigger collapse as major rents expire and CRE owners default on loans, etc. Exactly the behavior that contributes to our vacant ground-floor retail issue. Just lower the damn rent!

As much as I somtimes grimace at SS’ seemingly endless repetition of stock phrases – particularly with regard to commercial > residential conversion – at least it repeats coherent ones. Consider SFGate’s Bizzaro world take:

However, low demand for office space that’s driven more by work from home trends and the economy and not induced by lower rents, has enabled landlords to maintain current rent levels even though market conditions suggest otherwise.

That’s right: low demand enables high prices!

The defaults have already started. I read earlier today that a WeWork Venture Defaulted on their Loan for a San Francisco Office Tower:

This is in addition to Columbia Property Trust’s $1.7 billion default on seven properties that include two downtown San Francisco towers earlier this year.

Well clearly this is an outlier (in every sense). Just today there was a

storycolumn in the FT about how great everything is (“Commercial real estate is bruised but not broken“) – please ignore the barrage of negativity in the FT’s Comment section – you of course know what “Panglossian” means – and the fact that a picture of SF – just down the street from 600 California, actually – was captioned Not all CRE is the same. Office loans are most at risk…“This is a perfect example of market inefficiency with regard to supply and demand.”

More to the point, this is a perfect example of how supply and demand is not a “law,” but rather is a theory that works perfectly well on paper, ceteris paribus, while in the real world, nothing is ever ceteris paribus.

S&D conditions can put upward or downward pressure on pricing, but there are many factors (e.g. monopoly pricing power, asymmetric information, conditional liquidity, categorical errors, etc, etc, etc) that make markets “sticky” or otherwise ostensibly irrational.

They can’t lower rents because that in turn lowers the property value which sends shockwaves through the debt holding all the garbage together…for now. There will be billions in losses eventually but they will be involuntary. SF deserves everything coming its way. Maybe Ed Lee wasn’t so smart after all, selling out the city for Ron Conway, oh well, he’s dead, sort of like the city.

it’s a complete myth that SF did anything meaningful to woo or benefit the tech industry specifically. And if anyone says “twitter tax break”, they don’t really know what they’re talking about, because that was just general tax relief for any job growth in that geographic area that applied equally to any kind of business and had nothing to do with tech specifically.

That’s incorrect. While the Central Market/Tenderloin Tax Break applied to all businesses within the area boundaries, it was custom tailored to keep Twitter in San Francisco and benefit companies with similar compensation structures and rates of growth.

It’s not incorrect at all. There was nothing “custom tailored” about the tax break. It was a basic waiver of the city’s payroll tax for new hires. It’s about as blunt and non-specific as an incentive could be. In fact the city’s voters replaced that same payroll tax system with a gross receipts tax just a few years later. Were the city’s voters trying to lure tech and “selling out the city for Ron Conway”? Hardly. The only thing “tailored” about the mid-market tax break was the timing, because Twitter was threatening to leave town entirely to save on payroll taxes. San Francisco’s payroll tax was relatively unique and a disincentive to keep labor-dense industries (ie anything that is office-based) in the city. So yes that means tech, amongst a lot of other office-based industries.

It was a basic waiver of the city’s payroll tax for new hires that was specifically designed to keep Twitter, and other fast-growing, labor-intensive companies in San Francisco, the ordinance for which was custom tailored to expand the Mid-Market police foot patrol boundary by a block to cover Twitter’s HQ and provide an express service bus line between Caltrain the Civic Center BART Station, adjacent to Twitter’s HQ, during prime commuting hours.

And yes, the city’s voters were trying to lure tech companies, jobs, and wealth to the city.

Interesting bit of history there. Interestingly, the 83-X Muni line you’re referring to was duplicated by a free shuttle run by the landlord of 1355 Market St (the Twitter building). Always thought that was odd.

The Twitter tax break was the right call. Mid-Market is still in far better shape than it was 15 years ago. If Big Tech hadn’t moved in, I don’t think law, medicine or some other diversified set of industries would have. It would be continued to be empty lots and generally a wasteland.

Nothing in SF is in better shape than it was in 2008.

I was here in 2008. Everyone said how great the 90s were. I was here in the 90s. Everyone said how great the 80s were. Rinse, repeat.

And as someone who has lived in SF since the 1980’s I dont remember anyone in the 1990’s saying how great the ’80’s were. No one. Quite the opposite. Especially before Three Strikes passed. Street crime in SF reached its peak in the early 1990’s.

By the late 1990’s the first real signs that the demographic decline of the previous 40 years was over were starting to show and the City started showing real signs of pulling out it its post 1970’s shell shocked state. By 1998 SF was a hell of a lot happier and safer place than it had been in 1988. Or 1978.

Now the 1980’s were a huge improvement on the 1970’s. Which was basically one long nightmare in SF. But in the 1980’s SF was just a marginally safer version of downtown LA. So very much MadMax territory.

So for those of you new to the City and who were not around pre mid 1990’s, pre Three Strikes, the post Prop 47/57/ Boudin etc crime wave in SF has a long way to go. It will get a lot worse. A lot lot worse. Until Props 47/57 are struck down.

Yet another of Jerry Browns statewide disasters. There have been so many since 1975. So many.

I am a bit confused. Are you blaming Jerry Brown for all the problems since 1975, or are you giving Jerry Brown credit for all the progress since 1975?

I’ll bite. I could go on at length about how many abandoned gas stations and parking lots are now housing, how many new parks have opened etc but let’s stick with Mid-Market.

Mid-Market used to be mostly empty parking lots, abandoned buildings or low-end sunglasses shops. There were plenty of homeless people back then. It has added thousands of housing units, lots of new office buildings, restaurants and more. Was it better in 2019 than 2023? Yes, it’s declined since COVID. But it’s still a heck of a lot better than 2008.

Anyone who says SF is worse off now than it was in 2008 either wasn’t here in 2008 or was well insulated.

Anyone who says SF is better off now than it was in 2008 wasn’t here in 2008.

There were 98 homicides in San Francisco in 2008. There were 55 in 2022.

Now do all the other crimes Einstein. How about drug overdoses, car break-ins etc.

Most of the crime is occurring in the same neighborhoods that had the most speculative building activity and therefore the most gentrification, during the most recent “tech” bubble. Correlation is not causation, but wouldn’t if be foolish not to consider the apparent linkage if there are development, zoning, and economic policy lessons to learned?

“Most of the crime is occurring in the same neighborhoods that had the most speculative building activity and therefore the most gentrification”

Really? Most of the speculative building activity was in the Tenderloin?

As the ‘Loin has led SF in crime for as long as any of us have been alive, how about “increase” in crime? And yes, the ‘Loin has had some very high-profile, absurdly misplaced and mispriced luxe development: buildings which are still half empty, as a walk down some of the finest blocks on Market will reveal.

So are you blaming crime in the ‘Loin on new buildings? It’s been crime ridden, unfortunately, for a long long time.

Guns don’t kill people, buildings do!”

Do you have a point? Violent crime has declined as you point out, agreed! Property crime that the media love to scream about, like shoplifting, tagging, and public defecation, oh my! has increased. Gentrification exacerbates the already extreme wealth inequality that is the root cause of this increased property crime. This is most apparent in the neighborhoods with the most extensive recent “improvement.” The ‘loin has long had crime, and has also had its share of recent “improvement,” although not to the extent of other neighborhoods like SOMA and the Mission. Is this so hard to understand, or do you just like to quibble and lob “gotchas!”? The Dutch have a word, “mierenneuker,” to describe this type of rhetorical engagement.

^^Meant as a reply to SFRealist.^^

My point is that trying to blame crime on gentrification is a stretch.

Though if you’re a hammer, everything is a nail.

Based on office REIT valuations, a lot of these losses are already priced in…

But not yet realized, in terms of rents, earnings and market impacts beyond the values of the shares.

“..while it’s tempting to see, promote or editorialize an opportunity to convert all the vacant office space in San Francisco into housing, the conversion of existing office space to residential use still makes absolutely no economic sense for the vast majority of San Francisco buildings, due to the relative value of each use and the costs of conversion,” as we’ve outlined for over a year and others have finally started to figure out.”

This is such an interesting and arrogantly short-sighted point. Sure, the average office building in SF generated $72/sqft (vs. about $55/sqft residential), but to the *author’s own point,* that $72/sqft only clears about 70% of SF’s office space (for now, longer term, who knows how low that number goes).

Let’s oversimplify the math and say that the ‘true’ clearance rent for SF office space is 70% of the current average (since no office is 100% full but plenty of residential buildings are). By golly, now you’ve got $50/sqft for office vs. $55/sqft for residential. Compound that with higher financing costs driving demand for *cashflow now* and it’s maybe still a tight convert, but by no means “makes absolutely no sense.”

Now run the numbers for the cost to covert that office space that could yield $50 per square foot to a residential use, including all hard and soft costs, along with a loss of rentable space to cover residential building codes, new systems, and infrastructure. Subtract an allocation/amortization of that expense from the $55 per square foot that a residential use would yield and then factor in an expected return for the effort. By golly, it’s not going to be a “tight convert” for the vast majority of San Francisco buildings, it’s not going to make any economic sense at all.

By golly, it’s not going to be a “tight convert” for the vast majority of San Francisco buildings, it’s not going to make any economic sense at all…

Of course economics is all about making decisions based on the margin.

If that building can achieve $50/SF in market rents but can’t achieve stabilized occupancy greater than 60% (picking a number from air), then it might make sense to at least convert part of the building to another use. Markets tend to overshoot in both directions and commercial markets are particularly inefficient when debt markets aren’t working. Some Class A buildings could sell cheap enough that they could be converted.

Also keep in mind that the office building would have at least $20 per square foot in expenses. Add the cost of leasing commissions and tenant improvements (not considered expenses). The calculation for some buildings gets much closer as improved property values approach land values in some cases.

Not all buildings will be good candidates for conversion but some are already being considered (Warfield and 701 Sutter, among them). Expect architects, developers, and investors to seize on residential development modes that might have seemed crazy a few years ago (e.g. coder dorms/WeLive).

“Some Class A buildings could sell cheap enough that they could be converted.”

With that we completely agree. But we’re talking greater than 50 percent drops in value before most conversions would come close to penciling. And if/when that happens, there’s a whole host of other problems that will have arisen or arise.

Trying to convert half a building is often times more expensive, not less. And of course there are exceptions, including the Warfield, as we outlined earlier this year, but those buildings are currently few and far between and represent a drop in the bucket of vacant office space.

“With that we completely agree. But we’re talking greater than 50 percent drops in value before most conversions would come close to penciling. And if/when that happens, there’s a whole host of other problems that will have arisen or arise.”

We agree on that as well (see today’s Business Times).

Dude, coder dorms/WeLive weren’t deemed crazy a few years ago. Greedheads never stopped believing it was a viable business model and real estate mogul wannabees are still building them, even illegally (or without proper use permits).

Adam Neumann is very much still around after he was fired from WeWork; in fact Andreessen Horowitz handed over $350 million to his latest project (in which his company owns the property but magically fools people into believing that they are getting something other than being a tenant), reportedly its largest-ever check to a single company.

Wait…are you calling WeWork a success?

Before you or someone else here points it out, I acknowledge that there were other companies opening and operating co-working spaces prior to the founding of WeWork, and some of them were even doing so at a profit. WeWork’s advantage over them was sheer scale.

No, in my book WeWork is not a success, but I guess I have higher standards than the stock market. Define “success”.

My boss at the last company I was with told me multiple times: any executive who can get fired, leave with close to a $1.7 billion golden parachute and then retained as a consultant with an annual salary of $46 million before that executive then turns around and found a new startup with a $350 million initial investment from an A-list VC firm like A16Z is a success. The people opening up new co-working spaces still believe in that business model, and some of them (like my former boss) think that Adam Neumann is some kind of hero of late capitalism.

Your question implies that you probably have in mind WeWork’s inability to turn a profit, but of course there are other “platform” companies that built hugely visible brands, garnered widespread mainstream media attention, went public and still years afterwards are not earning a profit. Uber is the best and brightest example of that. I don’t call Uber a success, but the people holding those shares believe in the company.

Or maybe you’re referring to the vast drop in WeWork’s valuation since its failed IPO of company stock in 2019. I don’t know.

Define “success” for a startup. Is it building a company that provides a valuable service, returns value to shareholders and lasts for the long term? Or is it separating investors from their money and directing large portions of it to executives in various forms of compensation? WeWork was inarguably a success at the latter.

There’s another “s” word that applies to Newman: Scam. Like, buying commercial buildings and renting them out to your own company. Which operates on a model where you assume all the risk of taking on long term leases, sold on for the short term. The old joke applies: How did they make up for the losses? Scale.

Why does anyone think there is even demand for this kind of housing. Why would people want to move into a converted office downtown. There are buildings still being built and current empty buildings all over SOMA, those prices will have to be lowered, not sure even 50% does it given the additional costs.

The City wants to encourage office conversions where feasible in the downtown area. The Mayor proposed this. Many realize that jobs will not return to downtown in the numbers once there. The belief is the only way to “revitalize” the area is getting people to live there. Supporting local businesses and enlivening streets. Practically speaking most newer towers can’t be converted and, short of working downtown, who would want to live there? Especially young families. Good luck to the Mayor though The Chronicle is dubious the ship can be righted.

Newer towers don’t need to be converted: it’s older, until-not-long-ago-marketable properties that should be the first candidates; I’m thinking of something like the Shell Building – And I bring it up purely hypothetically, not that it’s actually been offered – quality construction, smallish floor plates and an historical pedigree that people might want to associate with. Older buildings that only meet one or two of these criteria I don’t know…maybe they can be offered on a “name-your-price basis” and hold BYOC(rowbar) parties.

What about converting office buildings to mixed-use residential? One elevator bank for residential floors and the other for office. I think it would be pretty convenient to work and live in the same building, being able to have lunch/ siesta time with only a few minute commute back home during lunch hours.

Seattle office market has problems too: “The share of office building loans considered ‘criticized’ spiked to 25.5% in the last quarter of 2022, from about 3.5% in the previous quarter, according to the real estate data firm Trepp, which analyzes data provided by banks. Criticized loans are those ‘getting the most scrutiny or being monitored the most closely from the bank,’ said Stephen Buschbom, research director at Trepp…’Places like Seattle, San Francisco, Washington [and] New York, have all struggled with the remote work, hybrid work environment’ reducing demand for offices, Buschbom said.

Oh yes sf, that sounds like a fantastic life, live and work in the same building so you never have to go outside an interact with the real world. You must also be a proponent of the 15 minute city, I guess you prefer the 2 minute version? Your idea is not even feasible in fantasyland.

If you work in an office you are interacting with people. You can still leave your house and office to go outside whenever you want outside work hours. What is the difference between getting into your garage and transportation pod (car) to wait 30-60 minutes in congestion to get to work. Why not just hop into another transportation pod (elevator) with no congestion and a 3 minute commute to work? All that time and money saved on commuting and transportation can be put to better life experiences.

Per the SFBT the vacancy rate is pushing 30%.

A 30% vacancy rate in conjunction with loans coming due/being refinanced at much higher rates portends owners defaulting on some of these downtown towers this decade. It has started with Build returning the land for One Oak to the bank to avoid foreclosure. Its India Basin project may see the same fate. The reality is the empty space may never be filled given the new remote work model which is here to stay – though some are still in denial about that.

Having been through two of these cycles (though this third one will be bigger and deeper), I can say with certainty that the other shoe hasn’t dropped.

Property owners can’t drop rents because there aren’t tenants at any price and the property owners’ loans include covenants which will be breached by rent reductions. Also, lenders don’t want to mark to market the CRE debt they hold, particularly now in the haze of the banking crisis (lender would be forced to mark to market if reduced rate leases are signed). Worst of all, there is no re-financing exit due to elevated interest rates and generally a credit freeze.

I am no bear, but the basic fundamentals here look incredibly bad going forward. The only hope is that commercial banks don’t bear the brunt of the looming losses (a lot of CRE debt is obviously securitized and also many non-bank lenders seeking yield entered the CRE lending game). In any event I expect multiple more deed in lieu (handing the keys over) and foreclosures to come. Then we will see lenders in possession trying to dump lender owned real estate if they can withstand the loss or valiantly try to drop rents. But all of this is a slow moving crisis.

It’s hard for me to see how SF gets out of this mess. The combination of voter-driven city mismanagement in all areas, combined with the trend of a higher proportion of remote work is deadly for the city.

Meanwhile other cities in the US have been growing in population and business sector diversity, and have YoY increases in home values.

Well, yes and no. SF has been slightly growing in population over the past year and a half or so (name link). There are a lot of millennials who haven’t checked out SF yet. Some of them will continue to come. Most major American cities have seen YoY price decline in home values. The city has been mismanaged. Cutting policing + the pandemic was really bad governance. Remote work is lousy for downtown, and it’s lousy for construction too as too many people issue noise complaints they otherwise would not be issuing. It’s tough right now. But, that said, many neighborhoods are thriving. And I’m optimistic there’s a way forward. I think some hard lessons have indeed been learned.

More accurately, “the estimated population of San Francisco proper decreased by 4,356 from July of 2021 (838,402) to July of 2022 (834,046) and is down by 36,084 or 4.1 percent since July of 2020, representing the largest percentage decline in population across all nine Bay Area counties,” the continuation of a trend that shouldn’t catch any plugged-in readers, other than the most obstinate, by surprise.

The U.S. Census says 808,437 for the very same month – came out in March, a revision maybe?

I believe they’re not so much “revisions” as different sources: IIRC the editor’s figures come from the State and the one’s you cited are from the Census Bureau (Federal). The former seem to consistently run higher than latter, but why there’s so much difference in the relative figures I don’t know.

That’s not more accurately. I said the past year and a half and I supported it with data. You came in and said “more accurately” and went with July of ’20. It’s not to do with what I wrote.

Unfortunately, you don’t seem to understand your data source, which isn’t for San Francisco proper nor for “the past year and a half,” as you wrote. It might help to look at the underlying source(s) of your name link, the fact that it’s based on data that was published last September might offer a little hint.

At the same time, the population data and trends for both the Greater Bay Area and San Francisco proper, as we first reported a quarter ago, are both accurate and timely, through July of 2022, which is the best and most accurate data at hand.

No, I do, and you inserted a timeframe outside of what I wrote. Now you’re parsing another aspect. It’s what you do. To me and others like me anyway. Old hat. Meanwhile you let novitiates run amok unchallenged with ill-considered words coming from agenda places based upon mere negativity.

Yeah the snarkiness of this site, including on the ed. side, is getting quite tiresome. Although this post has several dozen comments, most articles have very few … go back and look at posts from prior years (and when a lot more of the posts were about commercial real estate and not random residential sales) and you see a lot more commentary and interaction.

It’s a mixed bag with some cities especially in the SE seeing population and job growth and some home appreciation. SF will be one of the hardest hit cities as a result of the move to remote work. In terms of downtown recovery, it ranks last or close to last compared to other cities.

Axios just reported that SF’s population fell 7% from a peak of 869K to just over 800K last July. That trend will continue as will the job loss. SF will have to reinvent itself in the context of those parameters. And others. SF’s bloated government sector can’t continue. The City refused to discipline itself in the boom days – now discipline will be imposed upon it tax revenues collapse.

More accurately, “the estimated population of San Francisco proper decreased by 4,356 from July of 2021 (838,402) to July of 2022 (834,046) and is down by 36,084 or 4.1 percent since July of 2020, representing the largest percentage decline in population across all nine Bay Area counties,” as we first outlined and reported three months ago…

Ab Anno MMLXXV by Mr Peabody and The Wayback Machine

The die was cast the piper had come

The great unwinding had begun

From Tulips, Detroit to Oil and JDSU

So then went FIDI, Nob, Pac Heights and Bayview

Oh that a Friedmann or Haussmann had come

To help guide away from the manna gum

But one man’s loss is another man’s gain

And where we have landed shall there be no more pain

For the teacher today no sting did he bear

As he now buys a home in Alamo Square

Seems like the demand for less “blue chip” housing is down; I heard the new condo tower next to the Jewish Museum is 90% unsold, for example. So I don’t quite see what the demand for even more housing in older converted buildings might be.

And then the obvious question: almost 25 square blocks of institutionalized poverty and drugs called the Tenderloin. SF may not always have the tax base to “babysit” the problem, although legally, I think there’s a law that says sro people can be relocated if offered comparable nearby….but again, that would involve building a host of low income properties out in, say, Bayview, for example, which probably was the City’s long-range plan all along, but now, who could/would pay for a new “poor city.”

So I’m guessing there will be some conversions, some return to the offices (but not in droves), and SF will become something like Santa Barbara or LA’s Art’s district, if the human race lives that long, and various monies somehow pour in to fund the aforementioned. If I wasn’t over 60 I’d be looking up U-haul’s number, in all honesty.

“I don’t quite see what the demand for even more housing in older converted buildings might be. ”

There’s a historic glut of studios and 1BRs; the only need is for affordable 3+ BR family housing. These buildings won’t supply that, and they won’t provide the open space and other amenities such housing requires. The conversion “demand” we see here in the comments is from the real estate sector itself, such as loan officers, developers, and property hustlers: people who need work now that the asset bubble they’ve coasted on is collapsing.

Those “property hustlers” that you speak of run the game. It is going to happen.

As our host has shown, it doesn’t pencil out. Developers with currently empty residential buildings well know more studios and 1BRs will face high vacancy rates and put additional downward pressure on pricing, and there’s no feasible way to provide the amenities essential for family housing.

Developers will come hat in hand to the city for major subsidies for conversions. The political donor class that owns downtown property will clamor to git ‘er done, and they will use the media they own as a megaphone for it. However, with the collapse in collected taxes, there will be a battle to keep city services alive. it won’t play well with voters.

It will come down to this: do we shutter basic civic services in order to build more high-priced studios and 1BRs for WFH pizza delivery app style sheet coders, dried-up foreign capital flight, and short-term hospitality brigands? I’m dubious.

Yet many families chose to leave SF for better schools, less crime and more open space. Especially now with a significant portion of the workforce able to work remotely. I’m not sure the demand for 3+BR family housing is all that great.

Yes, truly the dreamy ease of navigation on WA-99 and I-5 and 15th Avenue are an endless source of bucolic contentment for families. Not to mention the fantastically rated public school system. [/sarcasm]

If you’re interested in an unbiased summary of how various cities downtown areas are doing now, the School of Cities at the University of Toronto used a combination of census and mobile phone data from all over North America to rank how well those downtown areas bounced bank from the pandemic.

San Jose ranked number 26. Oakland came in at number 49. Seattle was number 56. Guess which city came in dead last? You can see the bar chart summarizing their results at their Recovery ranking site.

Does “downtown Las Vegas” even exist (beyond being an assemblage of words like “purple dinosaur”)??

I was actually going to note the same for Bakersfield, but there is such a place, even if – like San Jose – it’s smallish for the size of what the city is now.

I guess SF’s goal now is to work it’s way up the list…lookout Cleveland !!

You’ve never checked out The Fremont Street Experience? If you have, that is located downtown. Btw, Paul Schrader’s 2021 movie The Card Counter has a scene set there if you aren’t familiar.

Basically, the area north of The Sahara and south of Owens Ave. is downtown, although the University of Toronto’s survey may count The Strip since that area is so crucial to the area’s economy and not located in one of the endless subdivisions of single family homes both inside and surrounding the city limits.

Yeah. A tourist town may be SF’s future – like Santa Barbara but w/o SB’s great beaches.

People are waiting longer to have kids, or not having kids at all. Dense cities are the most desirable places to be for those childless people. SF has a huge lead on every city sans NYC as a dense, walkable city with a good climate and an educated population. It needs to get even denser to make nightlife better and MUNI more effective.

In my opinion, as long as SF builds a huge amount of housing to boost taxes, population, beautification, etc everything will be fine. It may turn into a more residential city, but that’s fine. That’s why your quote from Ted Egan spooked me as apparently the math doesn’t work right now to build.

I saw that too. I’ve had conversations with several builder and developer types over these problems. How can building more cheaply happen? Even if CEQA and permitting time lengths get eased, and carrying costs lessened thereby, there is still the problem of worker’s comp being so incredibly expensive. Then you have raw materials issues. At least lumber came down. But gypsum sheetrock is off the charts expensive. You’re simply not going to have many people building these days because very few projects are going to pencil.

It’s going to require the City to pull out all the stops, almost a zero-interest rate situation.

– No affordable housing requirements

– Fewer height restrictions

– Fewer permitting costs

– Drastic reduction in turnaround times for permits

– Building requirement changes. The new thing YIMBYs are harping on lately is the requirement for two exit staircases as being unnecessary.

– Property tax breaks for a few years? a la the Twitter Tax Break for residential?

I can’t speak to materials costs.

There’s another major component that’s missing from your maths, a key component that’s at the foundation of every (re)development project, particularly depending upon one’s holding costs.

” It needs to get even denser […]”

Double down on the historic misallocation of capital! Even less diversified economy! Brilliant!

SF could be a utopia at the population density of Paris or Brooklyn. Demolish all of the single story retail businesses on commercial corridors across the city, build 5-over-1 housing, and perhaps the precious PDR space will be spared!

@Panhandle Pro – I couldn’t agree less! The best parts of SF are the neighborhoods. Noe, parts of Bernal, West Portal, some of the Richmond,… The dense parts of SF are the disaster areas. Dense and near transit sounds great, but then go to the mission BART stations and it’s like Mad Max.

Livable density requires strong and effective government and social norms. Compare a Tokyo subway station to 16th & Mission BART. The great parts of SF are great in spite of not because of the local government. This is a huge problem that the “build, build, build” people fail to acknowledge.

When I first came here decades ago I was given the advice that “Crime doesn’t climb” i.e. you are going to have better QoL up on a hill because the steepness discourages homeless/criminals/druggies. I found this to be true, but I also noticed that low density can have the same effect. The more sparse flat parts of the city can feel safe/nice becuse if there are few people out and about, then there is little reason for a criminal/homeless/druggie person to be hanging out ( no one to steal from or buy/sell drugs from). The standard retort to this is “It’s a city. Deal with it or move to the burbs/Marin” But I’ve been around the world and not all cities are like this.

If you have Tokyo law enforcement and social norms, then Toyko style density can be livable. But that doesn’t mean that Tokyo style density will be livable with SF law enforcement and social norms.

@Wilson – There’s a huge difference between Tokyo style density and Paris/Brooklyn style density.

The huge difference is that Tokyo had a population density of 6,158 inhabitants per Km² in 2015 and Paris had a population density of 20,623 inhabitants per Km² (2021 survey), so at first glance, Paris appears to be much, much denser. That probably wasn’t what you had in mind, kinda like when you read those planning studies that describe Los Angeles as one of the most dense cities in North America.

What you’re probably talking about is density of dwellings, but Panhandle Pro specified population density.

wilson, as I have pointed out here before, Tokyo-like social norms and enforcement of the same are possible to implement when you have a population like Tokyo has.

Only about 2.3% of the entire resident population of Japan are Gaijin. As of December 2020, close to 560,000 foreign nationals lived in Tokyo Prefecture, out of a population of over 13 million. In contrast, as of 2019, the percentage of foreign born residents in S.F. was north of 33 percent, over twenty eight percentage points higher.

Tourist sector already was the single biggest sector of SF economy pre-pandemic. Trade show activity at moscone center has taken hit with tech sector bailing out of downtown.

WeWork delinquent at multiple office buildings in downtown SF.

And their stock is down almost 65 percent year-to-date versus the S&P 500’s increase of over 8 percent during the same time period; they just got notified by the New York Stock Exchange that they are heading toward being de-listed. I still expect WeWork or some other “player” — perhaps a startup — to try and take advantage of all the vacant space in S.F.’s by trying some hack like throwing multiple desks on a floor of an underused office tower and leasing them out on a desk-by-desk basis. Just you wait.

Some troublemaker may actually try to take advantage of all the vacant space by actually lowering their asking rate. NAH!!! Too crazy.

Other SS comments suggested that mortgage terms don’t give landlords that kind of flexibility?

I’m sure there are plenty of loan covenants that have those kind of restrictions – hence why

they would be a troublemaker ! – but certainly not every one. And somewhere in SF

is a building or two that’s owned outright.

350 California, an office building currently for sale, is a good current example to put some numbers around office demand.

It’s a little less than 300k sf.

In 2020 owners listed the building for sale for +/- $250mm.

Now it has been re-listed for $120mm.

$400 psf for reasonably well-located 1976 office construction.

32% leased, radically under-utilitized. This is what people don’t want.

Union Bank (Mitsubishi Financial Group) owns the building and there does not appear to be a property-specific debt lien on the property. I mean, those guys know something about depreciating office buildings, right? This comment will not be published.

Wow, a >50% price cut is incredibly sobering