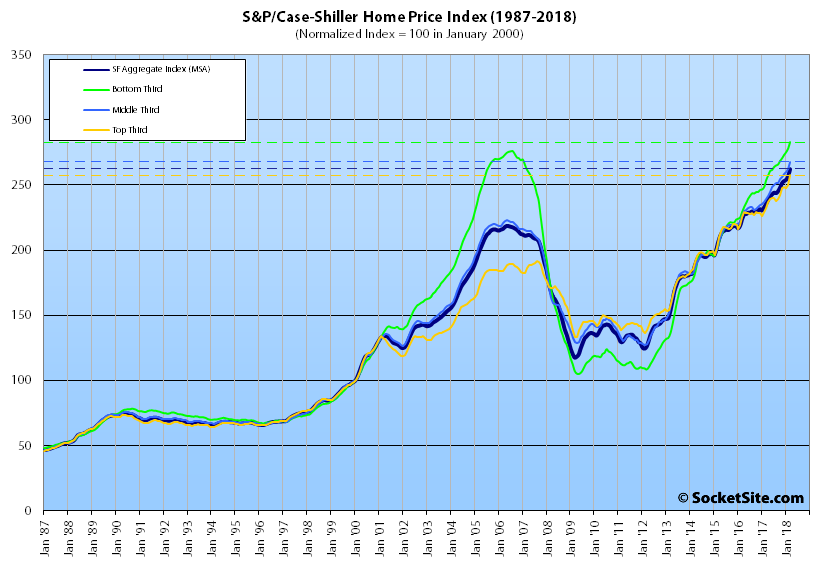

Having ticked up 1.0 percent in February, the S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller Index for single-family home values within the San Francisco Metropolitan Area – which includes the East Bay, North Bay and Peninsula – jumped another 2.1 percent in March to a new record high and is now running 11.3 percent higher on a year-over-year basis versus 5.0 percent higher on a year-over-year basis at the same time last year.

And having returned to its 2006-era high-water mark for the first time since the Great Recession in February, the index for the bottom third of the market ticked up 1.8 percent in March to a new record high and is now running 11.5 percent higher versus the same time last year, while the index for the middle third of the market ticked up 1.9 percent and is running 11.7 percent higher on a year-over-year basis and the index for the top third of the market jumped 3.0 percent and is running 10.9 percent above its mark at the same time last year.

As such, the index for the top third of the market is now running 34.6 percent above its previous peak which was reached in third quarter of 2007, the middle tier is running 20.0 percent above its previous peak in the second quarter of 2006, and the index for the bottom third of the market, which had dropped over 60 percent from 2006 to 2012, is 2.5 percent above its previous record high.

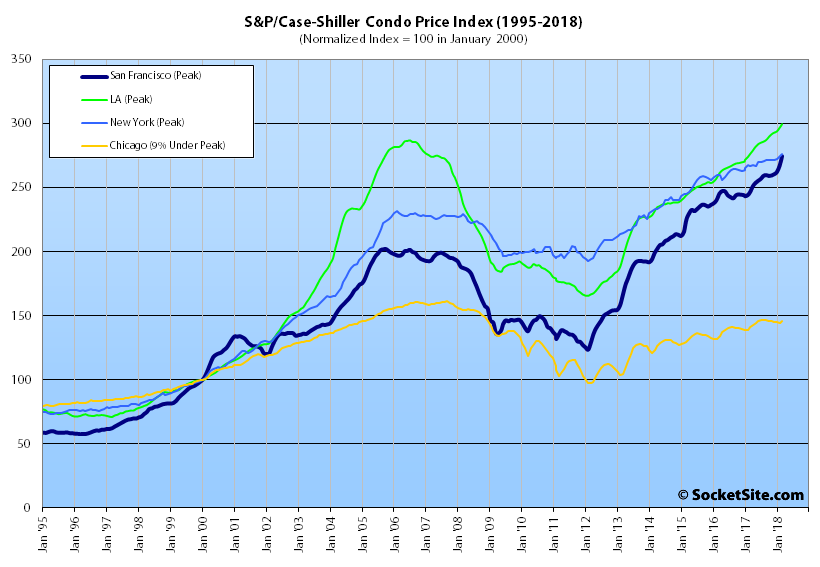

And having jumped 2.8 percent in March, the index for Bay Area condo values overall is running 11.3 percent higher on a year-over-year basis and 35.9 percent above its previous cycle peak in the fourth quarter of 2005.

For context, across the 20 major cities tracked by the home price index, Seattle, Las Vegas and San Francisco recorded the highest year-over-year gains in March, up 13.0 percent, 12.4 percent and 11.3 percent respectively versus a national average of 6.5 percent.

Our standard SocketSite S&P/Case-Shiller footnote: The S&P/Case-Shiller home price indices include San Francisco, San Mateo, Marin, Contra Costa and Alameda in the “San Francisco” index (i.e., greater MSA) and are imperfect in factoring out changes in property values due to improvements versus appreciation (although they try their best).

With the Uber IPO just around the corner…

Or not (but really, what’s another “pissed(off)” official…other than maybe being the million-and-first?)

Not just Uber. Come Sept of this year, Dropbox employees will be able to sell (180 days post IPO date). Uber, AirBnB, Pinterest and possibly Lyft are getting close and could all happen in 2019.

I believe many [people] overinflate employee options as the driver of everything. Options vest over a number of years, typically 5, for new employees, and many tech companies have such high turnover that many people leave before vesting, so an IPO means nothing to them. Early employees, founders and venture firms make out the most on an IPO, and this is a much smaller number of people.

This report shows many of the companies most people talk of have the most employees leaving well before vesting.

Not true. 4 year vesting is standard in tech, with 25% at the end of the first year. Anyone leading on the business operations side will get options as part of their comp, and many will receive additional grants along the way. An exit as large as Uber should yield enough of a payout for even late hires to put a 20%+ payment down.

Sticking with the math, what’s the actual number of said employees that either live, or would like to live, in San Francisco? Of those, what percentage already own homes? Of the remainder, what percentage are actually in the market for a home in San Francisco? And of those, what percentage will have the funds to qualify, and at what level, taking into account taxes, liquidity and recurring income for the required debt service?

Let’s look at the math. In 2017, around 2100 SFH and 2200 condos were sold in SF. Let’s assume if the number of buyers increases by 10%, this would move the market. Let’s say 10% of buyers are around 450 people (SFH and condos combined).

Now, Uber has around 3500 employees in SF. Dropbox and AirBnB have around 2000 each, Lyft and Pinterest have around 1000-1500 employees.

I would argue that if any two of these companies IPO in the same year, we should be seeing 400 employees that start looking for housing in and or around SF. Keep in mind that this employees are mostly young people in their 30ies and 40ties.

If anyone has better estimates or a better way how to think about this, I’m very happy to improve on my back-of-the-envelope calculation.

Including new construction and unlisted sales, the number of homes that traded hands in San Francisco last year was actually a little over 5,700 and the average age of a tech worker is around 30.

So based on your model, two significant IPOs in a single year isn’t enough to move the market. Correct?

Even a small liquidity event could move the market since the market is moved at the margins. It’s not like all 5700 sales had to be financed by tech IPO $.

I agree mostly with “taco” and will add more.

Yes, it’s true there are employees who come and go and the number of multi millionaires is not high. However, don’t lose sight of the long tail. There are recruiters at AirBnB, for example, who might net 100K post tax. With some savings, that’s enough for a downpayment. There will be thousands of people with a nest egg to make a downpayment all of a sudden.

Also, adding a new big public tech company to the pool has ramifications for years to come. Google, FB, Apple employees get big salaries *and* can sell off stock grants as they vest. There are many of those employees making 500K/year all in. Each time a company goes public, hundreds of new employees steadily get richer.

“thousands of people … “, a tad hyperbolic. Although living here my whole life, I’ve grown used the always exaggerated rhetoric surrounding the tech industry.

For those whose options even vest, many never get exercised and expire because there is a strike price that may not have been reached or passed to make exercising them worthwhile.

Even in tech nobody is just giving money away.

Based on what I’m reading above, sounds to me like IPOs do not benefit enough people to move the needle in real estate (especially SF). The economy in the bay area definitely, then, isn’t affected by the success in tech over the years. Maybe it’s only the salaries to explain why the peninsula in and around FB is extremely expensive…

Thousands of people is absolutely not hyperbolic. As a data point, I know relatively entry-level (i.e. < 5 years work experience with BS or MS) engineers who joined Google in 2004 (when it had already IPOed) and employeed about 3000 people. Their *initial* option grant would be worth $8M+ now. Or consider FB. Any engineer who joined before late 2011 got options/RSUs worth easily more than $1M. Many who joined after the IPO also ended up millionaires due to the stock rising almost 5x the IPO price. Most startups will initially allocated about 10% of their shares to employee stock, which means a public company worth ~$500B will likely have created at least $50B in employee wealth, although how that is distributed varies.

“sounds to me like IPOs do not benefit enough people to move the needle in real estate (especially SF).”

Remember that the US median home price is around $330k. The apple featured here today was bought at $2.6M and then fell to $2.0M.

The niceness of SF and higher tech incomes are very well baked into our housing prices. The real question is valuation (price/income). If someone tries to sell you Apple stock at a Price/Earnings of 1000 and then goes on about how great Apple is and how much money they make, while that’s all true, it’s also a distraction from the valuation elephant in the room.

There’s no rule that says you can’t over pay for a quality product.

Let’s do a little more math, since I’m kinda interested in getting a better answer to this too. I’ve been in tech many years so I have some background on this. I’m going to make some assumptions and do some rounding, but it feels like a reasonably educated guess. Feel free to poke holes in mine, or make better guesses about the inputs.

1. First let’s ask what’s the rate of tech employees that GET the money they need that will actually pursue SF homeownership?

I have no idea what this is but maybe some data mining can tell us. I think I’d swag 10% as realistic and possibly conservative given what we think we know about demographic, current attitudes and aspirations of home ownership in SF? Young tech workers who have the opportunity to buy may not all be itching to change their living situation and have a massive amount of their net worth be in an illiquid investment in this crazy market.

2. Now, how much does someone need clear from the IPO to realistically want to get in the SF market?

I’d venture around a $1M place (a bit below median condo price in SF) which means a standard $200k cash downpayment but also a $5000/mo payment for a 30yr fixed loan. I don’t know the risk profiles of the average young professional but I’ll suggest the average tech worker is not stomaching that monthly for their shelter. So, maybe those with less saved up / less cash compensation will go for slightly cheaper places, and those who do bite at this level have a bigger nest egg already or are later in their careers and have enough cash comp to afford the monthly (e.g. dual-income late-30s). So let’s say we want $300k after taxes, or $600k before.

3. Finally, if a company goes public, how many of its employees will gross $600k extra cash after the IPO?

Let’s take an example but representative company that has a few thousand employees (Dropbox, Uber) and IPOs at a valuation of $24B (twice as big as Dropbox .. but only 1/3 as big as Uber). How many employees will have (and sell) $600k in equity? This is 0.0025% of the company. Many later employees don’t stay the full 4 years for vesting so let’s say this must represent 2 years worth of stock, so they must have been granted 0.005% (if options are early enough, the strike price is low enough to not factor in too much). How many employees get this much of the company? The part of the option pool that goes to most lower-level hires to that point could be around 5% ownership (I’m less sure of this number though, would have to dig into some public cap tables to see). That means ~1000 people get that level of equity.

10% of 1000 people = 100 new homebuyers on the market. Not massive, but feels like it could have a small effect at the margins. There are some big error bars here though. Is my 10% number even close? How much money do people really need? And Uber is 3x the value of my example, would yield roughly that many more homebuyers. So the effect could be somewhat weak, but could also be a lot bigger.

At first glance, taxes would be one thing to consider. To net $600k cash, you need to gross much more than that. And given the steep slope of the pyramid, there are probably far fewer people that gross $1M than those who gross $600k.

And even with your first cut estimate of 100 people, they got this wealth probably over at least 5 years ( ropbox was founded 11 years ago) and could have easily already financed a house during that period. Contrast that 100 people with the fact that the number of people with a job in SF dropped by 3,200 last month alone.

And SF domestic out-migration was -2,689 over a year with san mateo & santa clara having a combined net domestic out-migration of -33,928. You can see how other factors could easily swamp the effects of a small number of people getting down payment money over a five year period.

Speaking of which, City Attorney Dennis Herrera has just issued subpoenas to Uber and Lyft to turn over records on whether they classify drivers as employees or private contractors. “The subpoenas follow the California Supreme Court’s recent ruling on the definition of an employee versus an independent contractor,” and “Herrera seeks proof that Uber and Lyft have lawfully classified drivers as independent contractors or provide their drivers with minimum wage, sick leave, health care contributions and paid parental leave.”

Last month, the California Supreme Court ruled that companies must classify their workers as employees, “unless the company can prove a specific worker: (a) works outside the company’s control and direction; (b) does work outside the usual course of the company’s business; and (c) has an independent trade, occupation, or business of the same nature as the work she or he does for the company.”

“The argument that these companies have tried to use in the past — that they’re just a technology platform — doesn’t pass the smell test,” Herrera said. “People go to Microsoft or Salesforce for software. People go to Uber or Lyft for a ride.”

Now, now, no one likes a killjoy; specifically someone who brings facts to an emotion fight. It’s no big thing: they’ll just shift money from their huge profits to pay for…what, they don’t have profits? No prob, just tap the bottomless well of VC.

And if it turns out that what they’re banking on – getting rid of the drivers – turns out to be something they’re spectacularly unsuited to do, then..well.. uhm.

Disconnected the emergency brakes for a smoother ride: I can’t imagine a better metaphor for UBER than that!

Fortunately, if (when) Uber or Lyft go public, you’ll be able to short their stock, make a killing, and afford whatever house you want.

If you are very brave. But make sure you’re not wrong.

Seriously, though, San Francisco is less than a rounding error for Uber. Uber owns 25% of Grab and chunks of car sharing companies worldwide. Uber will be fine.

“Uber will be fine.”

Will their driverless flying cars be operational before or after Elon’s Great Martian Migration?

That happens right after the tech economy collapses.

Uber lost $4.5B last year. They are dreadfully behind on the autonomous front. To quote scofflaw Travis Kalanick: “If we are not tied for first, then the person who is in first, or the entity that’s in first, then rolls out a ride-sharing network that is far cheaper or far higher-quality than Uber’s, then Uber is no longer a thing,”

Of all the theories why SF is magically different, the ‘IPO effect’ at least seems reasonable at first blush. Google IPO’ed in 2004, Facebook in 2012. You could look at the CS graph above and see a correlation there.

And in fact during the 2007 cycle, there was a line of argument that regardless of what was going on with the rest of the US, the up-slope here in SF was due to tech money and thus prices wouldn’t fall here. Obviously prices did fall here.

The Economist has a wonderful interactive housing price graph. Pick ‘US edition’ and then you can select various US cities, if you click ‘Income’ you can see the change in price/income ratio.

While looking at SF prices and the Google IPO you might see a correlation, but if you look and see that many other cities were bubbling up at the same time it points more towards a macro phenomenon. After all, why would the Google IPO be felt in Tampa? And the fact that the price/income ratio rose indicates that this was a case of momentum/exuberance not just a rise in fundamentals (i.e. due to increased income).

Fast forward to this cycle and you see the same thing. Maybe the 2012 rise here was the ‘Facebook effect’? But then why did the price/income ratio rise in LA, Denver and Miami right around the same time? And again, notice that this time around again the price/income ratio rose, so our higher regional incomes are all ready taken into account.

And even within a geography, it seemed a bit of a reach to tie prices in SF proper to MV based Google back in the last cycle. And here now we’ve seen a whole crop of SF proper apples performing far worse than the regional CS average, yet the IPO people are hyping up is SF based Uber. Granted it hasn’t IPO’ed yet (and it’s far from certain that it ever will), but it’s not as if the presence of Uber in SF is a well guarded secret. Markets can speculate about the near future after all.

Anecdotally, the reason that cyclical effects appear to dominate any ‘IPO effect’ is that while a rising tide raises all boats (i.e. momentum affects all market participants), you need a very specific set of circumstances for the ‘IPO effect’ to be felt.

Many people don’t work in tech, most startups fail, even those that don’t fail may not have capital structures/exits that deliver much to rank and file employees, even some winners of the stock option lottery may already be adequately housed and others may simply ‘take the money and run’ not wanting to live in SF (or even in the BA).

Even the timing of the liquidity event may not be significant. If you really thought it was the time to buy in SF, you could already have gotten zero down loans, and someone with a good income and a pile of vested options would be candy to most banks. Conversely, if you’ve endured years of sweat, stress and toil to get your payout (which as others have pointed out, for most is six-figure-ish, especially post-tax), you certainly don’t want to throw that hard earned money into the wood chipper of a declining market. The latest apple here shows someone that incinerated somewhere in the neighborhood of 3/4 of a million in three short years. “Vest it over 4 years and lose it over 3 years” is not the motto that techie strivers repeat to themselves.

“San Francisco Metroploitan Area” includes the East Bay? That’s so wrong. The East Bay has nothing in common with the city of San Francisco. SF is only about 12% of the entire Bay Area population. SF is not LA, NYC or Chicago. Those cities represent huge percentages of their entire metro areas. There are really three metro areas in the Bay Area. We need to have specific data for the three specific regions of the Bay Area.

“San Francisco Bay Metropolitan Areas”

There! Feel better now? The Eastbay, of course, has much in common with San Francisco, including a shared labor force and a glorious – if increasingly “again?” – NBA team.

I would strongly suggest Orange County is more distinct from the rest of the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area than the East Bay is from San Francisco.

The City of Los Angeles is 4 million people. LA County is much larger than that. Orange County shouldn’t be considered “Los Angeles” in any way.

The point is that LA County is huge while San Francisco County is tiny. Alameda and Countra Costa counties, which comprise the Oakland/East Bay region and have a combined population of 2.8 million residents, compared to 870,000 in San Francisco.

I never think of Orange County as “Los Angeles.” Orange County is widely known as “Orange County” the home of Mickey Mouse.

Tell that to the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim.

“The East Bay has nothing in common with the city of San Francisco” – it is really hard to find an area that is less affected by the business in a neighboring area than the East Bay to the SF/Peninsula/SV area. Why are all those people commuting west if they aren’t part of the same economy?

Most East Bay residents work in Oakland, Tri-Valley and Silicon Valley. Unfortunately, there are still far too many that clogg our entire region by trying to cross the Bay into SF. Also, the East Bay has its own theaters, sports arenas, shopping districts, museums, zoo, Airport etc. There really is not much of a connection to SF. They need to pin these analyzes to the specific SF, Oak, and SJ regions and markets.

There you go again, making mobility sound like a war crime. Most EastBay resident work in the EastBay – imagine that! – but a lot also work in the WestBay, the SouthBay, the NorthBay, the Bay itself (harbor pilots). There are even people from those areas who travel INTO the EB to work there, crazy huh?

Yeah, sure it might be nice if everyone could walk or skateboard to work, but that would mean moving every time one changed jobs, and while I’m sure there are many on SS who wouldn’t object to paying sales commissions every few years, many would rather spend their money elsewhere. So try to forgive the ambulatory for not making the BA seem like Cold War Berlin.

I just think the shunning of centrally located and transportation friendly Oakland, for decades, due to very unfair fear mongering, racism and elitism, has created unnecessary gridlock in the Bay Area.

SF-centric transportation planning and funding has caused the incredible gridlock we see today. If we had equal jobs to population in each of the three Bay Area regions we wouldn’t be seeing this congestion and downtown Oakland would be three times it’s current size.

“Oakland ranks highly in California for most categories of crime. Violent crimes including assault, rape and murder, occur from two to five times the U.S. average. The 120 murders recorded in 2007 made Oakland’s murder rate the third highest in California, behind Richmond and Compton”…. reality is not “fear mongering”.

You are quoting 2007 crime stats and we are in 2018. Also, last year Oakland had about 30,000 crimes while SF had over 60,000 crimes. Yes, it has been unfair, racist and elitist. Now, Oakland is finally booming due to the changing demographics which have now encouraged investment from the former investers and bankers who redlined Oakland for decades. Shame on thiose in the Bay Area who were a part of keeping Oakland down for 4 decades.

We should be using more current statistics, even though the stigma of a high murder rate will last for decades. The current numbers are the same number of murders in SF and Oakland, which means the murder rate is about twice as high in Oakland. Both cities have higher crime rates than San Jose or Fremont among others.

The “stigma” is made up due to a city having certain demographics. Has absolutely nothing to do with the amount of crime in a downtown area. SF averages about 400 weekly crimes within a one mile radius of city hall. Oakland averages about 70 crimes within a one mile radius of city hall. Look at all the development in downtown SF or downtown Chicago. “Stigma” really means an image conjured up by racist attitudes.

No, the stigma is individual home buyers deciding not to purchase in a place where they don’t feel safe. SF has a fairly large churn of people who arrive to the city when they get a better paid job than they can get elsewhere, but those who have kids often decide to move to areas that are more suburban in character. If Oakland is to be on either end of this specter it needs a better image – at this time it does not appear to be a career destination and it is not a suburban setting where most people like to raise their kids. Why did you choose to live in Oakland? Where you born and raised there or did something convince you to move there?

One mile radius to city hall, SF v Oakland, is a very forced and downright weird thing to go with given the vastly different geography, density and square miles.

For example, we assume not many crimes are committed inside of Lake Merritt. I’ll bet if you subtract those 140 acres Oakland starts to appear much more dangerous in proximity to its city hall.

You could do it for a half mile radius from both SF, and Oakland City halls, and downtown SF still has over 5x the number of crimes.

Anyone walking both downtowns sees that Oakland’s is far less threatening, far cleaner, with far less open air drug dealing and drug use. Oakland has been unfairly maligned and defined by a selective SF-centric media.

The “stigma” narrative coming out of SF is no longer effective as Oakland is now booming with residential construction and is also the tighest office market in the United States. The “Oakland is dangerous” nonsense can now be thrown out the window.

The stigma is not created by SF – it is a general impression across the state. If it is really as great as you say Oakland residents should be happy with the poor image as it keeps housing costs in check while they get to enjoy the wonderful and safe city.

So if you don’t live in Oakland, do you work there or visit often?

There is some truth with some “being happy” with Oakland’s distorted image. Some do believe the conjured up negative image does keep their rents lower than what they would be with a fair representation of the city by the media. I don’t go for the “let’s let people unfairly depict Oakland so my rent doesn’t go up” narrative. This is a selfish way to look at things. Oakland needs to be fairly depicted and it needs to be given credit for what it is as it excels at being the best city it can possibly be.

With one of the highest murder rates in the state it is hardly conjured up.

“we assume not many crimes are committed inside of Lake Merritt”

You haven’t lived until you’ve seen the gondolier knife fights on Lake Merritt – Friday nights at dusk.

Actually, as an informed reader would know, there actually WAS a murder committed IN Lake Merritt not to mention the ongoing “crime” of BBQWB (although technically speaking, I believe both incidents were outside the one-mile radius)

But now back to the actual topic of this thread, the CSI, and why the Bay Area looks so much like other areas, despite the (presumably) oversized influence of tech here…

11.3 % higher yoy, and 5 % higher the year before that resembles other areas?

Look at the longer term trend via the Economist link, not just this month’s data. Many areas have risen up at around the same time. (And don’t forget that an ever increasing crop of SF-proper apples seem to be doing far worse than the broader bay area average)

And if you think that the rise in price/income ratio is SF specific or you don’t even believe in looking at prices vs income, consider this quote:

““But the continuing run-up in home prices above the pace of income growth is simply not sustainable. From the cyclical low point in home prices six years ago, a typical home price has increased by 48% while the average wage rate has grown by only 14%,” Yun said.”

And if you don’t know, Lawrence Yun is the chief economist of the National Association of Realtors, not a group known for being overly bearish. Basically this is the guy who took over David Lereah’s job.

Being more uber-bullish than the NAR’s chief economist is like being more right wing and unteathered to facts than Donald Trump. It’s certainly your right to hold such a position, but realize how far out of the mainstream you are.

“11.3 % higher yoy, and 5 % higher the year before that resembles other areas?”

No, but the ~275 of SF is very similar to the ~275 of NY – tho I’m sure our 275 is better than theirs! – and not too different from the ~300 of LA. Of course it’s much higher than the ~145 of Chicago, and the many other places that are 100 (or less). I’m not saying the BA is typical, only that it doesn’t seem to be unique.

I said year over year. I said nothing about sustainability. But where is a high price area performing similarly? Seattle? Do you think Seattle’s run up is unrelated to its burgeoning tech industry?

And Portland, Denver, LA, Miami and San Diego as well? And all these places had IPO’s or other positive industry events at around the same time? And last time it was a bubble, but this time it’s just a set of happy improbable coincidences?

Portland, Denver, LA, Miami, and San Diego don’t look like SF or Seattle on paper, now do they?

If you see an effect that is common across cities, focusing on details which are different among them is more likely to show you what *isn’t* causing the effect rather than what is. Similarly, if you want to look to details such as natural beauty or salaries to explain an effect you should look at if these details rose and fell with the observed rise and fall of prices.

The NYT just ran a story about Vancouver’s housing market.

“Like many cities around the world, Vancouver is grappling with punishing housing costs that have pushed out large swaths of residents — and are causing distress among young adults who can’t afford rent today and take it for granted that they will never own a home.

Part of the reason is the attraction of Vancouver itself, and not just among Canadians. Between its natural beauty, its temperate climate and Canada’s liberal immigration policies, the city has become a magnet for foreign buyers, especially from China.”

Did Vancouver (and SF) have their natural beauty rise up in 2007 only to simultaneously fall in 2011?

“What makes these gains so remarkable is that unlike Silicon Valley, London or New York — where the presence of high-paying tech and finance jobs helps explain housing costs — Vancouver has relatively low salaries. ”

This is almost an advertisement for the need to look at price to income ratio. Last time the low end overshot on the rise and undershot on the fall, a pattern which seems likely to repeat itself. But while different in amplitude, last time all price levels rose and fell in roughly the same pattern.

“The figures show, however, that unlike other expensive West Coast cities like San Francisco, where the housing supply has long lagged behind population growth, Vancouver has consistently produced new housing. Over the past decade, the housing stock has grown by about 12 percent, while the population has grown by about 9 percent, according to the city.”

Supply obviously matters a bit, but in these last two cycles the surge of momentum due to high price expectations swamped the effects of supply. Suppliers chase high prices but even in the best case are limited in how fast and how much they can build, but capital and buyers chasing hot markets are more numerous and can move much faster.

I feel as if, though it took a significant hit, last time around San Francisco actually weathered the market shift storm differently than many other areas. Would you not agree? And the actual recovery took place faster as well. Did this have nothing to do with tech? and internet commerce models being local? Trillions of dollars were created, and they were created locally.

Absolutely. But I think the big difference is not between SF and the other high end (mostly coastal) cites, but rather between coastal areas and “flatland” areas. I see a 300k engineer levering into a $3M house in SF and an $80k engineer levering into a $800k house in a lower end tech metro as being mostly the same as far as housing cycles go. And higher tech valuations/productivity is already factored into that higher $300k compensation.

But as you drop down the income scale at some point the absolute level of income/wealth matters. If people are already barely sustaining a normal life at the top of a cycle, then any dip can cause a cascading chain of value destruction. The US median household income is about $60k, and that’s for a household and also means that 1/2 of families make less then that.

Though it may irritate the ‘endless summer’ crew that we see out-migration here, it’s actually a good thing. The curse of low end workers and low end regions is that people get stuck and don’t move.

Take that $2.6M Mission condo that dropped to $2M. Can’t be fun to lose 3/4M$, but other than price for all practical purposes nothing has really changed for the building or the area. The $2M resident is unlikely to be very different than the $2.6M resident.

During a downturn in most of SF, if you didn’t look at Zillow, SS or other RE news you might barely notice anything happening. Contrast that with areas that see vacancy, deferred maintenance issues, increase in crime and drugs, etc.

Bottom of the barrel areas in SF (Bayview, Tenderloin,…) will likely see some unpleasantness, but even there a bad neighborhood in a rich city (in a rich region) is worlds away from the plight of a completely economically depressed region.

I am curious to see what happens in the slightly better neighborhoods in District 10, 3, and 4 where people have paid some eye popping prices recently, yet these areas may still not be ready for prime time.

High priced is relative. Seattle’s median home price is 810K. SF’s is 1.6 million. Seattle’s run up is more broadly driven than SF’s. The population growth is about 3x that of SF’s and is one of the “other” factors. Also the economy more diverse and less dependent on tech though tech has been a prime driver this past decade.

Without Amazon Seattle’s run up would have been a lot less – one large company is dominating the market – that is not diversity.

And the RE market is in bubble territory, we can just hope for a softer landing this time, one that doesn’t set the whole economy back 8 years.

And why should we hope for that – or more precisely, why should we expect it – when the Fed for the past decade has been re-inflating a bubble, decimating savers incomes and distorting capital allocations ??

I wouldn’t expect a soft landing, but I would hope for one because a depression or recession means people loosing their jobs, their homes, and a general decline in the well being of everyone. The real estate tycoons will be fine (i.e. the Donald) while the average Joe feels the pain.

And they will continue to feel the pain – either on Sunday’s when they peruse the ‘help wanted’ ads or at EOM when they pay their c’cards: you can’t have a healthy economy when “growth” is funded by one half – really more like 90%, I s’pose – borrowing from the other to buy things. There’s no shortage of money in the country, there just a shortage of…well “fairness” (yes, I cringe using that word) in how it’s allocated.

To a certain extant though, the damage has already been done on the up-slope.

It might seem better at first to avoid a nominal price drop while inflation and incomes play catch-up, but having sellers refuse to capitulate on price doesn’t make buyers any richer. So usually transaction volume collapses. Fewer transactions impacts construction. Why build places with high sticker prices if no one is buying. New homes usually spur consumer spending and renovations, which decline when no one is buying homes. Mobility decreases as it’s harder to relocate to follow new opportunities. Notwithstanding Lawernce Yun’s unusally candid departure from the ‘There’s never been a better time to buy’ mantra of the RE industry, many from the RE industry like to relentlessly cheer-lead higher prices. But again, it doesn’t seem like a scenario with high wishing prices and rock bottom volume is all that beneficial to industry participants.

A slow multi-year decline also might seem “soft”, but what of all the people who get suckered into buying on the downslope? What of people who struggle to make payments on their top of the market purchases only to endure years of Chinese water torture of their equity drip-drip-driping away? And you can have years of reduced mobility and productivity loss while people stress and hunker down in the face of their dwindling equity.

There’s a very good case to be made that the best scenario would be a quick price correction followed by years of normal growth. That wouldn’t be painless either, but the damage was done during the up-slope, it just isn’t felt until much later. You feel great while you’re throwing back vodka shots, but there aren’t many good options for avoiding the next day’s hangover.

The diversity within tech is growing in Seattle. It’s no longer a secondary tech hub but a primary hub. There is a lot more than Amazon though it has been taking so much office space that many more office projects are in the works to accommodate all the tech companies, aside from Amazon, desperate for space. The military presence is the third largest in the US. That brings a boatload of support jobs with it and provides a region-wide stability. It also provides a stability to the housing market as many, many military retirees choose Seattle to retire in/to. The recently merged single port authority (Seattle and Tacoma) manages the second busiest port on the West Coast and one that is capturing share on the West Coast. RE is not in a bubble in Seattle. Seattle proper will hit a million residents in a little more than a decade .That population growth ensures a bright future for the region.

Not that SF is in a bubble but, unlike Seattle, it is in a plateau. Yun’s comments ring true though most dismiss or ignore them. The big run-up in the middle and bottom tier areas of SF came from techies being priced out of the top tier areas. The price surge is not going to be repeated as these areas become too expensive themselves for techies. There is not the wage growth to insure big appreciation going forward.

Anecdotal. A home on my street in pneumonia gulch sold in the last month to a tech couple who were priced out of the better SF areas. They are 30ish, bring down over 300K/year and have one child. They barely managed to purchase the home (family loaned/gave them money to help with the down payment) and the 1.35 million was for a home needing 250K worth of work. Work they will have to let slide for several years as they can’t afford to do it now. As middle and bottom tier areas become barely affordable for techies prices will stabilize and appreciate slowly for perhaps a long while until salaries can do some catching up.

“Work they will have to let slide for several years as they can’t afford to do it now. As middle and bottom tier areas become barely affordable for techies prices will stabilize and appreciate slowly for perhaps a long while until salaries can do some catching up.” <– a soft landing

In the last cycle, even once there was widespread acknowledgment that there was a huge valuation problem with prices, some people floated the hypothesis that prices wouldn’t actually fall in nominal terms. Instead, they postulated, that prices would hold flat while inflation and rising incomes slowly brought valuations back down to earth. People have been shown to have an irrational unwillingness to sell a home at a loss (sticky prices), so this wasn’t an entirely absurd hypothesis. But obviously this didn’t happen and prices did fall.

Anecdotally, some of the same buyer mentality that drew people into the market without much long term thought or planning also made it easier for them to exit (“easy come, easy go”). People who leveraged into the market had little equity and not much skin in the game. Any social stigma to defaulting or selling out at a loss (which sets a declining comp for all your neighbors) seems to have been much reduced compared to prior eras.

And from a purely mechanical point of view, notice that when you have a very large run up, you can easy have the market drop even when individual owners would prefer to hold out.

If you get in at 2017 prices and plan to hold firm when you see the first signs of market weakness, what about the guy who got in at 2016 prices? He can get out even at his prices and in doing so setting a comp which makes your position untenable. And how can you hold firm against the tides of the market at 2016 prices when the guy who bought at 2015 prices is all too willing to kneecap you to get his capital out?

And what of investors? Holding on to a unrealistic selling price irrespective of opportunity cost is widely thought to be an irrational behavior, though common to emotionally attached homeowners. Investors are much more willing to ignore suck costs/prior mistakes.

All of these factors seem like they are in play this time around as well, so I don’t give too much weight to the hypothesis that we will avoid nominal drops in prices. And while many ‘endless summer’ types try to misdirect our attention away from all the ‘bad apples’ featured here, I think that even if they don’t yet represent the average sale it’s a very significant test of seller mentality that so many sellers are willing to sell out at a loss. If it was different this time, you’d expect to see that by now.

I agree that the damage is done and prices are at unsustainable levels. Increasing interest rates should dampen prices without hurting people with fixed rate mortgages. I think the policy goal should be to discourage further price increases without creating a crash, which is easier said than done. A recession always destroy resources with plants running below capacity, higher unemployment etc.

Even if SF prices has topped out as this site suggests, the greater Bay Area still see large gains as do most of the country.

The cure for the low homeownership rate is lower prices. Every government policy that purports to make housing more affordable actually makes it less affordable.

But if you are a policy maker and you determine that prices are irrationally unsustainably high and then decide to keep prices propped up at that irrational level, you are just condemning a whole new set of buyers to buy into that level.

And only people who really have no choice will want to do so, causing transaction volume to collapse.

And if you look at the people involved in constructing, financing, selling, furnishing, renovating and maintaining homes, there’s a pretty good case that keeping healthy transaction volume is much more important than keeping prices propped up.

Additionally, having a healthy home market aids greatly in mobility. And giving people the freedom to move somewhere where their income exceeds expenses is a huge boon to economic growth.

Any irrational exuberance for asset pricing that people did in the past is a sunk cost.

“And if you look at the people involved in constructing, financing, selling, furnishing, renovating and maintaining homes, there’s a pretty good case that keeping healthy transaction volume is much more important than keeping prices propped up.”

The tools to lower the prices are Higher interest rates, removing the mortgage tax deduction, increasing property taxes – all the things that makes home ownership less desirable. By implementing these you will drastically decrease sales volume and subsequently prices. What policy are you going to implement that will lower prices without decreasing volume?

As a current home owner I don’t care about the interest rates as mine is fixed, but I do care a great deal about the interest tax deduction and property taxes as they affect my ability to keep my home with the sunk cost.

“Higher interest rates, removing the mortgage tax deduction, increasing property taxes – all the things that makes home ownership less desirable.”

Less desirable at current price levels. Absent intervention, prices will just fall to a level where these things are factored in.

And to be clear, I think that trying to force prices lower for “affordability” is just as misguided as trying to prop prices up.

You can’t just look at some output variable and force it to whatever level you want, you have to look at what you’re doing to keep it where it is.

If you were to state by fiat that all homes would be kept at 90F, for people in Arizona that might just mean keeping their window open, but for those in Alaska you might end up subsidizing a huge heating bill.

The real goal should be reducing energy consumption. If people like it hot, they can move to Arizona. If Alaska is too cold they can either pay out of their own pocket for heat or move.

Your home loan is someone else’s bank deposit. Interest rates need to hit a level where there is enough incentive to save, banks make an adequate profit so that they don’t require constant taxpayer bailouts and there’s enough of a ‘risk premium’ to cover people who default. If you want the government to keep the 30 year mortgage market functioning, prices need to hit a level where most people can sustainably afford them. Inevitably, some people will lever themselves to the hilt and get bailed out later by IPO options, a rich uncle or whatever, but on average this will not be the case.

I am not sure that I get what your point is. Interest rates and taxes are macro economic tools that are actively used by the government. They will affect housing prices, but not necessarily the cost of home ownership – a decrease in interest cost as we have seen in the past 10 years will be offset by increased prices on resale homes, so you can say that they are propping up prices. However, increasing interest rates will not decrease construction cost so while there will be a downward pressure on resale prices as fewer people can afford the homes at current price there will also be less supply of new homes to the market…

So while you desire lower prices of homes I do not see what your path is…

If you look at your heating bill and it turns out you are spending $4.5 Trillion to keep your house at a temperature of your choosing and you’ve had multiple furnaces blow out and start fires because of how much over capacity that you are running them, you have to end up concluding that you are doing something very wrong.

Having to do $4.5 Trillion of QE and multiple bailouts, and implicit debt guarantees in order to keep rates low is an indication that something is wrong. And just like a huge heating bill, all that work to keep rates low has costs and consequences.

And again, it’s not about keeping prices low. Look at rent control and how many unintended consequences it has had, and how they are constantly needing to pile on law after law to patch holes in the dike keeping market pricing at bay.

If people are over-leveraged to get into homes that are bigger or in better locations then they can really sustainable afford, there is a continuum between that and them having no house at all. A construction worker building a 3,000 sqft home is just as well employed building 2x 1,500 sqft homes. But the longer you have people building and buying product of the wrong type in the wrong locations, the bigger the hangover you get when the bill comes due.

So what should be done about it? 7 more interest increases by the federal reserve over the next 2 years? Put a lid on the tax deduction of mortgage interest at about $10K?

My suggestion for policy makers is to close up shop. Let the market set the cost of interest rates, no pawning off private risk to the public taxpayer, flat tax with no deductions for anything or anyone. Your doom and gloom blackmail has no basis in fact. In 2010, the depths of the housing collapse, we saw an 11% spike in first time homebuyers over the historic norm.

Maybe a financial disaster should be treated in the same way as a natural disaster. Targeted time-limited aid and assistance to those affected.

If a city below the water-line floods, you do want to help those people out and move to higher groud. But going off and building a new city still below the water-line is counterproductive.

Policy makers need to help people out who are suffering from the mistakes of the past, not repeat the mistakes of the past.

Re: “…policy makers…close up shop. Let the market set the cost of interest rates, no pawning off private risk to the public taxpayer…your doom and gloom blackmail has no basis in fact.”

In fact, policy makers did let “the market” set interest rates, etc. and the result was The panics in 1873, 1893, and 1907, the last of which eventually lead to the creation of the Federal Reserve as Gilded Age political leaders came to their senses. So your suggestion has already been tried and after several attempts turned out to be unworkable in practice and that’s why policy makers have “a shop” in the first place.