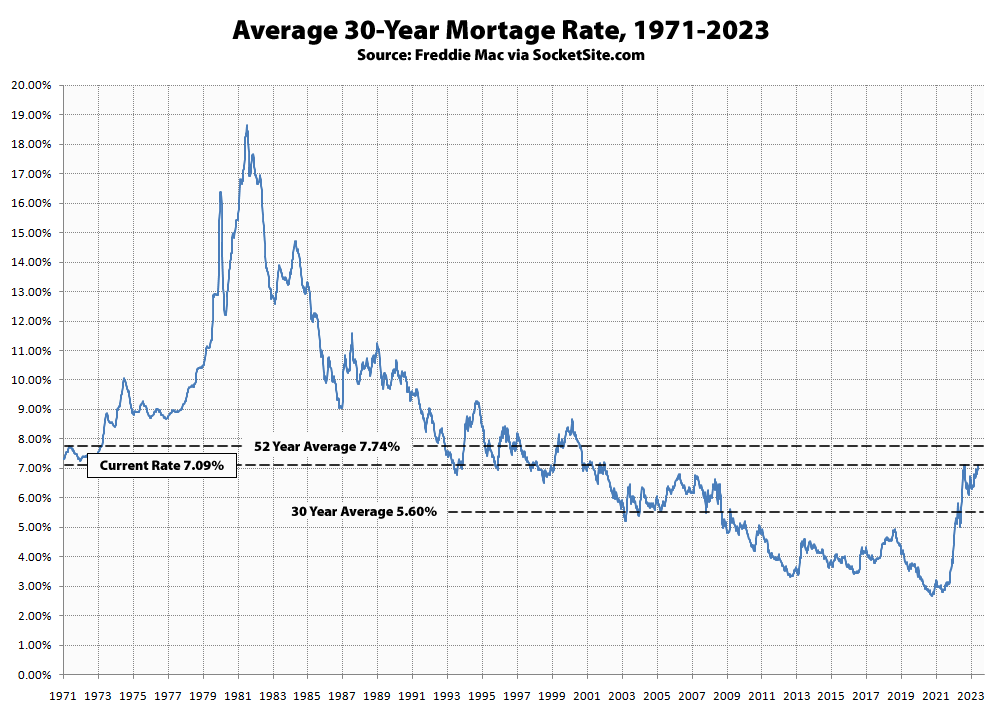

As projected, the average rate for a benchmark 30-year mortgage ticked up 13 basis points (0.13 percentage points) over the past week to 7.09 percent, which is 196 basis points higher than at the same time last year, 444 basis points, or nearly 170 percent, higher than its all-time low in early 2021, and the highest average rate since April of 2002.

That being said, the current 30-year rate is still below its long-term average of 7.74 percent, with the probability of an easing by the end of this year having dropped to 5 percent and the probability of another rate hike having ticked up to 36 percent.

As we outlined back in the fourth quarter of 2021, when the average 30-year rate started with a three, higher mortgage rates would lead to less purchasing power for buyers and downward pressure on home values, not simply higher payments for buyers, none of which should catch any plugged-in readers, other than the most obstinate or easily mislead, by surprise.

Now that we have arrived at “the 7 handle” on the average rate for a benchmark 30-year mortgage, let’s fire up the wayback machine and see what certain people projected to be the future peak of interest rates a couple of years back:

Never say never again.

To be fair, a lot of the pundits on cable TV at that time were saying that the U.S. economy would come to a halt if mortgage rates were to go above 5 percent, so The Fed would have to cut rates before the 2 percent target was reached. But here we are with no cut in sight, and except for those directly involved in selling real estate, the economy looks to be pretty resilient.

This is next-level commenting. You’ve been sitting and waiting on this one, ready to pounce! Bravo, Brahma. I was wrong.

From Mortgage rates could hit 8%, economists say, citing a worrying sign not seen since the Great Recession:

I don’t know how technical analysts quanity “easily going above” a rate level, but I think we’re going to find out after the next FOMC meeting in The Fall.

Yeah…I have some concerns about his methodology. Also, assuming that inflation holds at recent levels, it seems like the Fed might be near the top.

It seems ironic (at best) that housing costs are one of the prime drivers of the inflation that’s scaring the Fed … and the huge increase in interest rates is causing one construction project after another to no longer pencil out, so fewer new housing units will be constructed than would otherwise have been the case.

Imagine paying 7%+ on a 7 figure mortgage…good lord…

The owner of one of San Francisco’s biggest apartment towers, the 754-unit NEMA property is facing default.

Don’t be so closed mouthed, would that be Crescent Heights?

If so, word on the street is that their loan had a fixed rate of < 4.5 percent, so they can’t blame rising interest rates or their floating rate loan for their troubles.

I would also suggest that many of the people renting at that complex at Tenth and Market were probably laid off from their jobs since the middle of 2022, probably including some people who were dismissed when Elon Musk reduced Twitter headcount by 80 percent, which btw, some commenters around here praised him for. When those residents continued moved out of NEMA, it wasn’t because the amenities in the neighborhood have deteriorated since the pandemic.

Rising interest rates, coupled with rising vacancy rates, means no ability to re-finance. More to follow.

CRE contagion has crossed the street and is now starting on residential. Trinity and the Hub’s see-through sarcophagi can’t be very far behind. There are thousands of vacant units up and down Market St and throughout SOMA; eNEMA is only one of many such half-empty buildings. But lets build more unaffordable studios and 1BRs for twenty-something pizza delivery app stylesheet coders who moved away and aren’t coming back, because, why again?

just curious, how do rising interest rates affect an already finished building?

Don’t think one needs to be Aswath Damodaran to be able to see there are a number of scenarios that can affect the value for an already finished building caused by rising interest rates, even if the owner has a fixed-rate loan. A likely one for NEMA goes something like:

1. Interest rates rise, providing an attractive opportunity for folks who usually invest in fixed income and who, since the popping of the bubble in deliberately obscure financial securities directly tied to subprime mortgages circa 2007, have effectively been forced to invest in equities since bonds paid close to zero.

2. Less money is therefore available to fund speculative startups and other money-losing companies which traditionally employ lots of well-paid, so-called knowledge workers in S.F.

3. Startups and other companies in this category respond to Wall Street analysts implicit and explicit demands for cost-cutting with layoffs.

4. Many of those people laid off from such companies are newly-arrived to S.F., and some of them haven’t yet acquired their own homes, so they rent shelter at so-called luxury buildings like the 754-unit NEMA property.

5. As tenants move out, vacancies build up at the building, directly depressing revenue, which gets reflected in the building operator’s income and cash flow statements.

6. Continuing on this trajectory leads to a situation where the total revenue from rents is less than the amount required to service the debt on the building, the owner can’t refinance their loan because now interest rates are higher than when the building was originally financed and the property value is lower (due to depressed rents), so the owner defaults.

7. The lender takes back the building after a foreclosure and marks the asset to market, reflecting the actual revenues derived from the depressed rental income from tenants.

The lender puts the building on the market at a new, significantly reduced price, and voilà: when the transaction closes, the building is valued at a new, lower amount.

1 bed, 1 bath, 757 ft.² apartments at the 10th St complex are currently asking $3,580 per month.

If/when the 754-unit NEMA property defaults, the lender can take the property back, mark their newly acquired asset to market and drop any restrictive covenants on the loan(s) impeding the ability of asking rents to move lower to the point where the market clears as described in the Econ 101-level Supply and Demand models that real estate people and their naive supporters so often tell us we should believe. The City arguably has too many overpriced luxury rental buildings for the number of people actually working here with the ability to pay those prices.