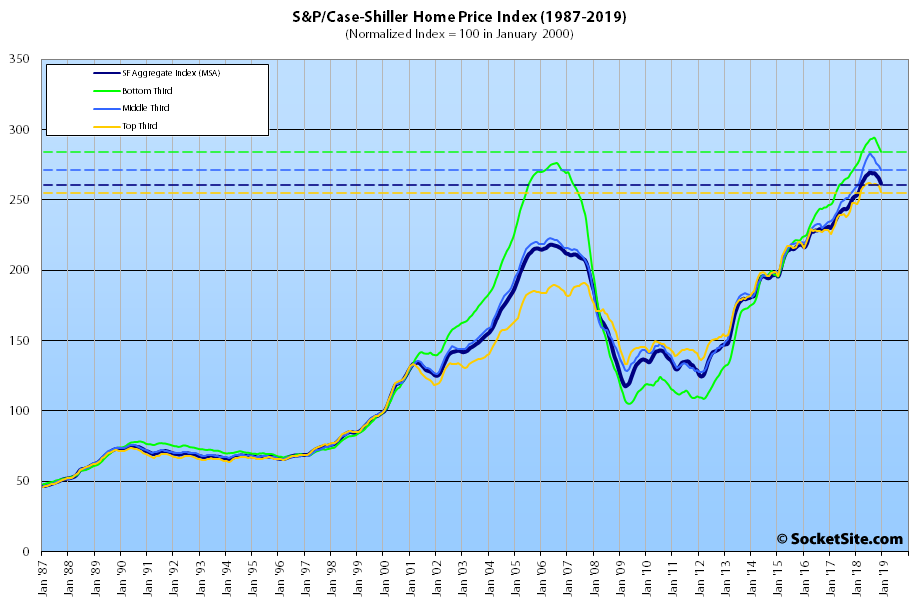

Having dropped another 1.4 percent in December, which is the largest month-over-month decline in seven years, the S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller Index for single-family home values within the San Francisco Metropolitan Area (which includes the East Bay, North Bay and Peninsula) shed nearly 3 percent in the fourth quarter of 2018 alone and its year-over-year gain has dropped to 3.6 percent, down six (6) percentage points since the third quarter of last year and representing the smallest year-over-year gain since 2012.

For the third month in a row, and only the third time since 2011, the index for the bottom third of the Bay Area market has dropped over one (1) percent on a month-over-month basis, dropping 1.2 percent in December and pushing its year-over-year gain down to 4.0 percent, a drop of nearly seven (7) percentage points since the third quarter of 2018.

The index for the middle third of the market shed 0.9 percent in December and is now running 5.2 percent higher on a year-over-year basis having dropped 6.1 percentage points over the past quarter alone.

And the index for the top third of the market dropped 1.7 percent in December, its largest drop since the start of 2012, and its year-over-year gain has dropped to 3.1 percent, down six (6) percentage points from 9.1 percent at the end of the third quarter.

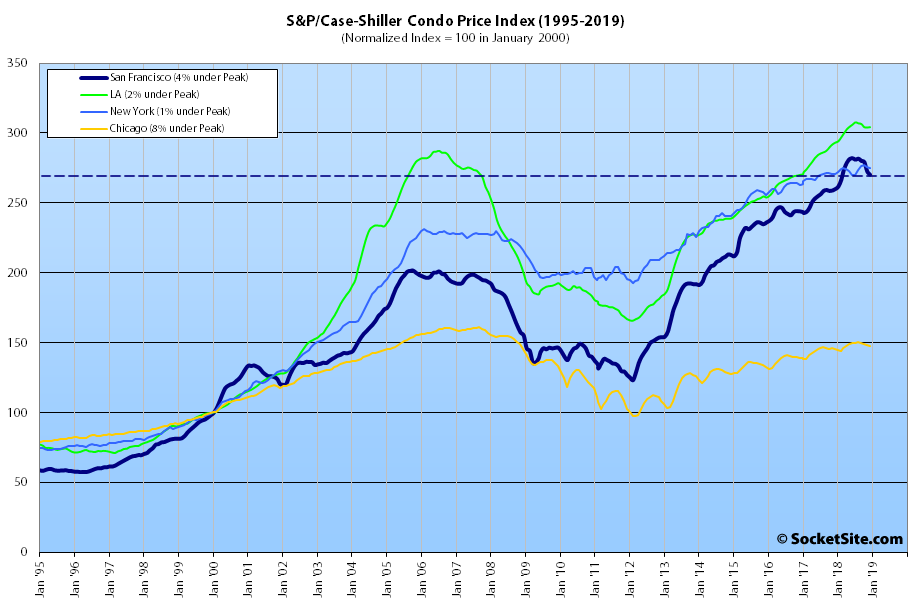

At the same time, the index for Bay Area condo values shed another 0.9 percent in December and is now running 4.2 percent below this past June’s peak but remains 3.9 percent above its mark at the same time last year (and 34.0 percent above its previous cycle peak in the fourth quarter of 2005).

As we first noted in the third quarter of last year, Las Vegas is still leading the nation in terms of home price gains, up 11.4 percent year-over-year versus a national average of 4.7 percent, with Phoenix in second place (up 8.0 percent) and Atlanta now in third (up 5.9 percent).

Or as added to the notes from the Managing Director and Chairman of the Index Committee at S&P Dow Jones Indices today: “Currently, the cities with the fastest price increases are Las Vegas and Phoenix. These are a reminder of how prices rose and collapsed in the financial crisis 12 years ago.”

Our standard SocketSite S&P/Case-Shiller footnote: The S&P/Case-Shiller home price indices include San Francisco, San Mateo, Marin, Contra Costa and Alameda in the “San Francisco” index (i.e., greater MSA) and are imperfect in factoring out changes in property values due to improvements versus appreciation (although they try their best).

All the homes that sold last month were on busy streets.

All the homes sold in the San Francisco MSA were on “busy” streets?? My reply gets deleted but Tipster post stays???

“It’s not different this time” is always a good place to start from. And I’ve long thought that we’d spend a year or more kicking around the top on this cycle just as we did in the last. Prior to the last two cycles homes were viewed as being stable safe investments (‘Safe as houses’ was an expression), so there was good reason for many to be in denial as the 2007-era boom sputtered out. While there are obviously speculators and young rootless singles in the housing market, for many people decisions on buy vs rent vs move elsewhere are complicated by many factors, jobs school/childcare, friends/relatives. Not decisions that can be made quickly. Companies planning headcount based on cost of living and employee interest or disinterest in various locations can take even more time. All these factors seem to anecdotally contribute to slower changes in the housing market.

But conversely, it does seem from looking at the apple harvest that sellers have compromised much more and sooner on price then I would have expected. Demand seems to have gotten quite a chill. Realization that there has been a dramatic change in the tone of the market has spread past niche RE blogs such as this one, but is not yet a mainstay of mainstream media coverage or of general dinner party talk (at least among people wth no professional connection to real estate or economics)

On balance, I still think it’s most probable that we kick around the top a bit. After all the top (or for that matter the bottom) was not tabletop flat, and this could just be a big ripple. But I think we should be watchful for a situation where the time at the top is much smaller than last time.

With 6-8 IPOs this year (Uber, Lyft, Stripe, Pinterest, Airbnb, Palantir, etc), I would strongly advise folks looking to buy a home/condo to take advantage of this dip. Once the fun money goes around, you are going to see a significant rise as newly-minted millionaires and deca-millionaires start buying up property. The supply picture in SF right now is bleak: fewer than 600 homes on the market now, which is incredible. What do you think happens in Q3 when these startups IPO?

In terms of the current supply (and demand), the actual inventory of homes for sale in San Francisco is at a 7-year seasonal high and ticking up (while pending sales are down).

After a trickle of rain, precipitation in the Death Valley Desert is at a 7-year seasonal high. Does that make it a humid place?

Keep in mind that this so called ‘IPO effect’ has not really been visible in the data. In the 2007 cycle, SF generally rose and fell along with the rest of the country. And in this cycle, SF rose and has turned the corner generally along with a host of other cities.

Also note that the iPhone was introduced in 2007, arguably the most successful and profitable tech product of all time, and with it a spate of staffing up, stock windfalls, knock on effects for suppliers and contractors. And yet all that did nothing to stop the 2007 downslope.

People have covered this before, but in broad strokes in a bay area region of millions, not that many people get a significant payout, many of them are already housed. And in general this market has not been capital constrained, you can already get no-down/low-down loans. And the source of your funds self-made/parents-familiy/IPO/”Rich foreigners”/… doesn’t really change the market dynamics. Buying on the upswing provides a bounty to all while a market downslope is an equal opportunity destroyer of capital.

Yes, and far fewer non-early employees get big exits anymore compared to the past, due to multiple rounds, liquidity preferences, etc. It’s really a small number of people that could maybe move a local market a bit, but not the entire region.

by fewer do you mean like 1500 at Juul splitting $2b in December

But that’s only $1.3MM per person. And there are 625 homes on the market. Hmm, makes you think ?

I suppose that end of December is a bit late to show up in the case-shiller numbers for December, but surely we should be in the throes of the ‘Juul Effect’ as we speak? With this to be reflected in the data in short order?

We shall see I suppose…

Do you think 1500 people at Juul got an even split of $2b? I think you have some assumptions about exactly how this is done. It is not even close.

I suggest you read on the web about what to expect re: equity as a startup employee. Title, experience, time of joining, personal negotiation are all key. In most cases equity is a mere promise, and can be totally unfulfilled based on later events in later funding rounds, etc.

Also, there’s no guarantee that these IPOs happen. If the federal government keeps shutting down, for example, they won’t go forward.

it will indeed be interesting to see how these IPOs affect the market. This should generate at least 1,000 post tax millionaires.

will be curious to see how the IPOs impact the market. this will generate at least 1000 post tax millionaires and probably at least 200 post tax decamillionaires.

The ‘IPO effect’ is a total myth, but nice try SF real estate agent.

It isn’t a total myth. It’s frequently overstated, but “total myth” goes too far. In a nutshell there is evidence that supports price increases proximate to work locations, consistent with IPO timing. What is interesting this time is that many of these are in SF itself.

“It found that after the filing date, average home prices within a 10-mile radius of headquarters rose by 1 percent more than home prices throughout the same county. After the company went public, the index rose an additional 0.8 percent. Surprisingly, there was no additional gain after the lockup expired.”

Look at that against the backdrop of the size of the 2007 and this current housing cycle. If we’ve already seen the 1% bump from filing and we can look forward to a 0.8% one time bump upon IPO, that’s really nothing.

And supporting the point that those who would have wanted to buy would have already bought: “Their surprising results about the lockup period also suggest that pre-IPO shareholders “change their housing demand when their wealth changes,” not when their liquidity increases, and that they “can finance their home purchases based on their illiquid wealth,” the authors wrote. “Banks in California may not be very restrictive in originating mortgages to entrepreneurs and workers at startup firms because of their relatively rich experience with this type of consumers.””

Many people have pointed out here how much easier it has become to tap pre-IPO wealth. Even the study authors predict a smaller impact than the allready small 0.8%.

“Hartman-Glaser suspects that the current crop of IPO candidates might have a smaller impact on home prices than those in his study.

“The flow of information from financial markets to real estate has improved,” since the 1980s, he said.

And companies are waiting so long to go public, by the time they actually file for an IPO, the prospect of new millionaire buyers might already be baked into real estate prices. Now, if IPOs from Uber and the rest are bigger than expected, that could cause home prices to rise, he said.

Hartman-Glaser also cautioned that “most of our results are for Silicon Valley, where the housing stock is very different” than San Francisco.”

I’m really not sure why you felt the need to cut and paste and to then interpret. Experts are doing so in the actual source. For example, I note you left this one out for some reason” “Theoretically, the Facebook IPO could have increased prices in Redwood Shores by 8 percent, he said.” Also your SF take is pretty much exactly what I wrote. So, yeah, no thanks.

What I quoted from was an actual study. The other actual study found:

“It found that two years after the IPO, the price of “expensive” houses in a ZIP code within a 2-mile radius of the IPO headquarters had increased by 0.7 percent more than homes in the surrounding area. These are homes in the top third price-wise. The IPO did not affect the prices of less expensive homes, said co-author Larry Fauver, an associate finance professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.”

So a 0.7% increase over two year post IPO for top tier homes and no effect for middle and low tier homes. The Zillow thing is essentially a blog post. And if you look at the source post it doesn’t even mention the 8%, that’s just his off the cuff musings about what’s “Theoretically” possible. And note that it’s about 10x the size of the effect that the actual studies found. The actual Zillow blog post only calls out: “This faster growth translated into an extra $29,800 in appreciation for the typical home in these Facebook-employee-heavy areas compared to homes in the rest of the Bay Area.”

I supose that could be 8% of a $377k house, but how many FB millionaires are living in $377k homes in the bay area?

Sure, the synopsis is a blog post. The study itself did the following: ” Using data from the Census Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics program, we identified the 1,360 census tracts that were home at the time to employees who worked in the four census blocks containing Facebook’s offices in Menlo Park, just south of San Francisco. Because the vast majority of employment in those four census blocks is accounted for by Facebook, it’s likely most of these employees were Facebook employees.”

That is just a direct quote from the blog post. The blog post links to no study that I can see.

So there were two published academic studies up for review by their peers that tried to control for many confounding factors and they found some very small effects. And there was an offhand quote by a PhD student moonlighting at Zillow based off a blog post that posited and effect an order of magnitude larger then what was found by the two studies. And you were wondering why I picked the two studies to quote from?

i know very few people who have tapped pre-IPO wealth. i think its only those on the tippy top

Maybe in the past, tapping into pre-IPO wealth was difficult requiring lawyers and bespoke contracts. But more recently there have sprung up secondary markets, which in some cases companies have given employees the green light to go and use.

But that’s a bit moot anyway, because this assumes that using non-liquid IPO wealth is the only way these people can get into the housing market. Most people use leverage to get into the housing market and plenty of people with no such windfalls in the pipeline even get low-down/no-down loans. What you should really be asking is: How likely is it that these people really wanted to get into the housing market, but couldn’t?

And the study that Ohlone California pointed us to (perhaps inadvertently) confirms what you’d expect.

“In summary, the evidence supports an expectations hypothesis, in which the original shareholders without liquidity constraints change their demand for housing consumption at the IPO filing event. The evidence also supports a wealth hypothesis, in which the original shareholders change their housing demand when their book value of wealth is determined in the stock exchange. However, the evidence does not support a liquidity hypothesis, in which the original shareholders change their housing demand only when they can monetize their book wealth. ”

They saw a small effect upon IPO filing, a smaller effect upon IPO and nothing at all upon the liquidity event.

It was three studies, not one, all based upon past IPOs. Here we find you summarizing that “nothing at all” and “evidence does not support a liquidity hypothesis,” are not synonymous.

Maybe approximately nothing at all would have been better.

“but approximately zero after lock-up expiration.”

That was “are synonymous.” Anyway, approximately zero now. Sigh.

Put it this way, how many newly liquid buyers you think it might take to effectively roil a market segment for a quarter?

What this chart proves….. even if you bought San Francisco real estate at the top of the curve and it’s highest price ever, in mid 2006, you would still be far ahead financially today. Conversely if you did not buy and kept your cash on hand, inflation would have reduced its value by 25% today.

Yeah, that’s all true but buying at a market peak entails a real opportunity cost…for what you might have done with the incremental down payment and/or mortgage payments. If you enter the housing market and pay $850K for a home that is $750K 18 months later (assuming you are not simultaneously selling another home), you’re out $100K. This becomes more important as you approach retirement and have fewer opportunities to earn-back or save the difference.

And if your income is variable based on cyclical factors that also affect real estate prices, buying at a market peak can have devastating consequences.

Buying in 2006 or buying in 2019 are not the only options.

Yes, it’s best to buy low. I mostly do. But even buying high will put you way ahead of never buying. FYI, if you don’t sell, you are not out that 100k in your example and it will recover later most likely. Only if you sell do you lock in paper losses. Getting upset by paper losses is an amateur investor mistake.

Opportunity losses are real. If you pay too much for a house then you don’t have the money for something else. You can’t philosophize your way out of that.

Appreciation losses are far greater if you don’t buy in. In 1987 the median home price in SF was $175,900. Even if you overpaid by 20% ($35,180) it hardly matters in the end, when in 2018 the median price was now $1,610,000. That little alleged opportunity cost, was in the end a stellar investment.

Sam – if you had taken the $211,080 for that house and instead invested in the S&P 500 in 1987, it would now be worth 2.1 million. So you could wait and go and buy the house now and have $500k left over.

This doesn’t taken into consideration property taxes, financing costs, tax deductions, etc., which make it a more complex picture. You really need a more detailed model to determine if it makes sense, and they are out there.

I generally agree with you that property can be a valuable investment in a market with consistent and continuously increasing relative scarcity. But I think you’re making a poor argument about “missing out” because you really aren’t seriously considering opportunity costs and your example seems backward.

The New York Times has a nice buy-vs-rent calculator that lets you vary multiple factors (expected price appreciation, inflation, investment return, etc.) Under most reasonable assumptions I’ve tested it doesn’t make sense for anyone in SF who has been in a rent-controlled apartment for more than a few years to buy right now.

You forget, you did not have $211,000 to buy that house with in 1987. You only had a $42,000 down payment and financed the rest.

This comes up here so often it’s annoying. Yes, you can assume that someone didn’t have to pay the entire $211,000 to buy, but so what? Gee Ess could have taken the hypothetical $42,000 and levered it up to put into his large cap index fund in 1987, too. The interest rate would probably have been higher than for a mortgage, but using leverage in the stock market is hardly unheard of. People were doing it in 1987 and still do so today.

You also have to factor in the cost of paying rent on a monthly basis since 1987 if you put the money into the stock market. Rent for 30+ years in San Francisco would add up to a large number.

“Buy now or you’ll be priced out forever.”

Do you subtract cost in rent from opportunity cost?

All of which brings us back to the actual data, topic and trends at hand: indexes for Bay Area home and condo values continue to drop.

Some slowing on the West Side possibly the last couple months

My House: 3 bed 2 bath 1800 sq ft, SFH in the Parkside

Avg quarterly price estimates taken from average of Zillow, Redfin, Realty Trac, Realtor

Date Avg Est Change

12/31/2016 1,319,674 0.90%

3/31/2017 1,298,666 -1.59%

6/31/2017 1,383,720 6.55%

9/30/2017 1,461,344 5.61%

12/31/2017 1,482,538 1.45%

3/31/2018 1,505,114 1.52%

6/30/2018 1,544,789 2.64% Peak

9/30/2018 1,492,483 -3.39%

12/31/2018 1,490,324 -0.14%

2/26/2019 1,346,465 -9.65%

you could look at it that way, or could say; one of only 9 houses to ever sell over $2mm sold in the last week with the 3rd highest $/ft.

In related news, Bay Area Home Sales Hit an Absolute 11-Year Low, Medians Prices Drop.