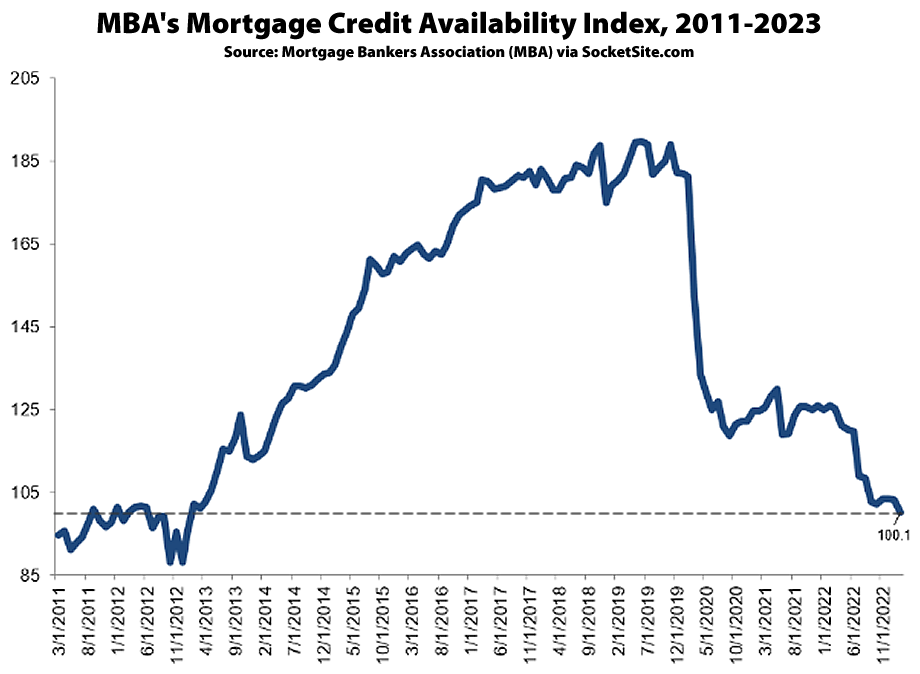

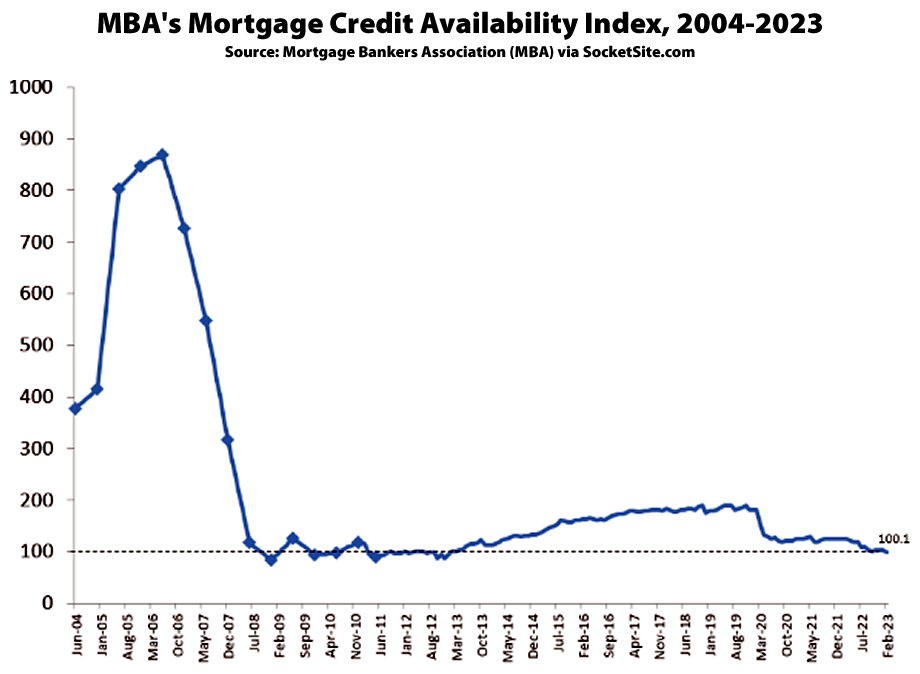

As indexed by the Mortgage Bankers Association, mortgage credit availability in the U.S. dropped to its lowest level since January of 2013, with “all loan types seeing declines in availability over the month” and the index for Jumbo loan availability having declined the most, driven by an “ongoing trend of shrinking industry capacity” along with “a reduction in refinance programs offered for low credit score and high-LTV borrowers,” in light of “this volatile rate environment and potentially weakening economy.”

And while the recent drop might seem insignificant relative to the drop from the ridiculously loose lending standards circa 2005, the indexed availability, which doubled from late 2012 to 2019 and is based on borrower eligibility, has since nearly halved with the benchmark 30-year mortgage rate having more than doubled.

Crickets from the SF RE fluffers.

Well it’s a US chart and notes that refinancing is a large part of it.

what part of SF sales is this chart?

Sparky is right. SF is its own republic and full of ultra rich moguls who never borrow money, not even for a house. Tightening credit across the world is not going to affect the local RE market, and it’s not like the City depends on Silicon Valley money, which just became 10x more difficult to obtain.

That’s not what he said. And Fred Mack up there going “fluffer” is pretty lame. Do we really need to be vulgar and dismissive while talking opinions about SFRE ? sheesh.

Anyway, taking a look at that chart, some of the lower figures compare to periods of all time high activity here in SF, 10/1/20 – 6/1/22 — that was quite the run here in this market. But it’s at the lower end of that spectrum. So yeah, sure, this chart shows a decline since then. I’d hesitate to be so arch while implying some direct correlation. As I said the other day, Wells Fargo jumbos remain relatively inexpensive and available. What, do you think mortgage interest rates are going to go up from here, now? Why would you think that?

I wouldn’t say that mortgage rates are going to rise now, let’s say over the course of the next couple of weeks, but I they will in the medium term, say between now and the end of the calendar year. And the reason I think that is pretty simple to understand.

The Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers increased 6.0 percent over the last 12 months, down from January’s 6.4 percent, but not close to The Fed’s 2 percent target (I realize that The Fed doesn’t use CPI, but headline PCE will be similarly not close to The Fed’s target rate). This means that The Fed will continue to hike the federal funds rate and mortgage interest rates nationally will increase in response to that.

If for whatever reason The FOMC doesn’t follow through with the expected quarter point rate hike at the March meeting, then all bets are off.

the 2% fed target is hogwash. 3.5-4% inflation is completely reasonable as a goal and not likely to kill the economy

It’s true that there is a very good argument that the actual inflation rate (within reason) matters less than the stability/predictability of the inflation rate. So a 4% target is probably not much different than a 2% target. But the killer is changing the target. If the Fed gives up fighting inflation because its getting hard and goes from a 2% to a 4% target, then why not later give up again and move the target to 5%, then 6%,…

And if there is not much downside to a higher target, there probably isn’t much upside either. It seems that people asking for a 4% target don’t really want a 4% target per se, they just want the fed to give up and hope to avoid the pain of getting back to their original target.

This sort of thinking was the bain of the inflationary crisis of the 70’s. That ended up dragging the crisis on for a very long time as the Fed would almost kill inflation, give up, inflation would rear back up, causing the Fed to do another tightening cycle, the Fed would cave in the face of economic pain, give up,… Until Volker decided to take things all the way to the finish line and finally end that inflationary cycle.

As Milto Friedman said, it’s not a question of if you will pay a price in order to end inflation (You will), it’s a question of if you will pay that price only once in order to end inflation.

Expanding on this. Think about how much our current problems are the actual rate hikes themselves vs the abrupt about face from “inflation will be transitory” to a series of rapid rate hikes. Given sufficient advance notice and consistent policy, banks and businesses should be able to hedge or otherwise deal with changes in interest rates. But going from “inflation will be transitory” to rapid hikes to “our work is almost done” to “we surrender, lets up our inflation target” would render any credibility of fed messaging worthless.

You can always find some group that would benefit greatly if they could influence fed policy one way or another. But in general, unstable/unpredictable monetary policy is a deadweight loss for the economy as a whole. The value of money and interest rates affect everyone. If everyone is forced to essentially try and forecast future interest rates and/or monetary policy in order to best run their lives and business then this causes great amount of effort to be expended for essentially no economic benefit.

wilson’s reply was actually better than what Jerome Powell came up with when he was asked a version of jimbo’s question during the news conference following the December 2022 FOMC meeting. From that transcript:

I call this “sputtering”.

It’s worth noting that The Fed isn’t trying to get the inflation rate back to 2 percent this year. If you look at the March 2023 Summary of Economic Projections, which is the most recent one as of this writing, (scroll down to Table 1. Economic projections of Federal Reserve Board members and Federal Reserve Bank presidents), you’ll see that the median Core PCE inflation projection for December of 2023 is 3.5 percent, and next year is projected to be 2.5 percent.

then i would argue for lessening the degree of increase. would prefer .125% increases as opposed to heavy hitting .25 and .5 every single time. whats the effect of overshooting, killing the economy and then starting cuts quickly after?