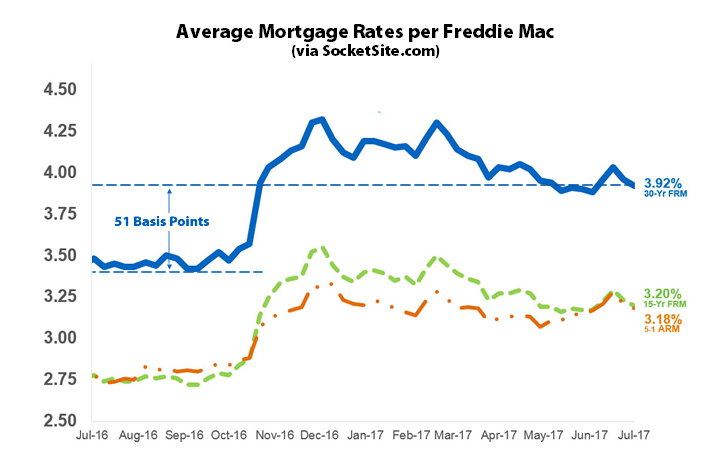

Having ticked up to 4.03 percent two weeks ago, the average rate for a benchmark 30-year mortgage is now back down to 3.92 percent but remains 44 basis points above the 3.48 percent average rate in place at the same time last year and 51 basis points above last year’s 3.41 percent low, according to Freddie Mac’s Primary Mortgage Market Survey data.

And the probability of the Fed instituting another rate hike by the end of the year is down to 53 percent, according to an analysis of the futures market.

The market remains surprisingly certain that inflation will remain at historic lows for the unforseeable future. I’m familiar with the secular stagnation theory and I believe demographics explain a lot of underlying drivers of long term inflation. At the same time, if we learned one thing over the past 10 years is that we do NOT understand inflation as well as we thought. The monetarist theory of money supply as the main driver of price changes has been put into question by the experience of the last decade.

Therefore, how can the market be so certain long term rates will remain so low for the next decades given the following conditions:

– close to record low unemployment

– late innings of a long recovery

– rapidly rising wages for low income earners

– announced deleveraging of central bank’s balance sheet

– close to record low unemployment

(Huge numbers of wage earners voluntarily leaving the workforce.)

– late innings of a long recovery

(With the vast majority of gains accruing to asset owners.)

– rapidly rising wages for low income earners

(This is not borne out meaningfully across the economy. Increasing pay in coastal megacities goes to housing, not to savings or investment or generalized spending.)

– announced deleveraging of central bank’s balance sheet

(They’ve announced it and it will be slow and steady. It’s much easier to rein in a growing economy with higher rates rather than stoke a stagnant one with low rates. In terms of political acceptance, many sectors like easy money, fewer seek higher long term rates. The Fed won’t win any plaudits by squashing a wheezing growth story.)

If you think the market is wrong, it’s pretty easy to put your money where your mouth is and short some TLT’s.

We won’t see broad inflation as a problem until wage inflation is a widespread phenomenon. The low unemployment rate nationally overstates the strength of the economy given the large % of potential employees who have (perhaps temporarily) opted out of the workforce. Gas prices are down. Food prices are low. These are lifelines to low income populations mired in opiod abuse and hopelessness.

[Sarcastic optimistic tagline here]

Too much focus on policy, the US economy runs on the consumer. Weak job quality vs quantity (gig economy, part timers, lack of benefits etc). Rising cost of essentials (housing, health care, education) far outpaced weak wage gains. Wealth effect of low interest rate policy heavily skewed towards the already wealthy. Cultural move towards experiences vs consumption. Deep government dysfunction does not lend confidence. The only hope I see for real inflation would be a return of manufacturing (see Foxconn) since Chinese wage growth has upended their equation.

Of course besides demographics, the other deflationary biggies are automation, shift from oil to renewables, rise of emerging markets, plus our massive debt is a drag on future growth.

I acknowledge all the points above. There are plenty of issues still outstanding and I’m not promoting more rate hikes. All I’m stating is that I’m somewhat surprised that 30 year mortgage rates remain below 4% under current circumstances.

Here is the good news on wage increases.

That is good news but are the poorest Americans going to drive inflation? I’d say the middle class is needed to drive inflation and they are the ones getting squeezed. Look at the labor force participation rate of prime working age males, this jibes with my own experience, very qualified people who have found it better to be stay at home dads or scrape by with gigs etc because after taxes it’s just not worth the trouble.

The inflation calculation is an intentional joke. The calculation methodologies regularly change so that inflation will never meaningfully increase. Otherwise social security, pensions, etc. would all have to increase their payouts (the CPI-W cost increase to Social Security this year is 0.3%, pure comedy).

Just look around at the massively increasing costs of housing, education, medical care/drugs, food…and tell me that inflation is 2% a year. That’s just flat out absurd, and anyone who believes it is a total fool.

The CPI inflation data have consistently proven by alternative measuring methods to be very accurate. True that housing, medical care, have gotten pricier. But loads of other things have gone down in price. A tank of gas costs far less than a few years ago. Same with airline travel. Same with clothing and shoes. Laptop I just bought for my daughter cost about half (and is far better than) the one I bought three years ago. Food has even gotten cheaper (other than, perhaps, SF restaurants. Go to Safeway). I wish you were right. The economy needs more inflation, and it’d be great if it were there and “they” were simply hiding it from us. But it ain’t so.

The gas price claim seems to depend a lot on which time frame you use (although to be fair you did specify “a few years ago” so that appears to be technically correct). And of course being a thoughtful person I know you’re not committing the common – though nonsensical – error of “adjusting for inflation” and then saying that’s the “real price”.

As for the “economy need(ing) more inflation”, when I was growing up, we’d have given our whole 50c/week allowance to have the rates we have now: the younger generation…sheesh!

Agreed that generally one cannot credibly adjust for inflation and claim the “real” price. However, in the context of this discussion, that would be perfectly proper. “another anon” points to a few examples of things whose prices have risen faster than the inflation rate. So countering with examples whose prices have risen, but less than the inflation rate, would be fine. The examples to which I pointed happen to have dropped in price by any measure, even nominal prices. It’s a common error to point to anecdotal evidence (like housing or medical costs rising faster than the inflation rate, ignoring the many other components of the rate) to try to “prove” a broader point. The BLS methodology to develop the CPI is solid.

lol. Next you’re going to tell me the U3 unemployment calculation is valid even though the labor force participation rate is close to the lowest levels measured over the last 40 years. So 94 million people in the U.S. are eligible to work but just don’t want to.

Yes, clearly we need to find a way to force people to want jobs. I bet if we eliminated social security benefits we would see lots of disabled and retired people rejoin the workforce. This would then make U3 more valid…somehow.

That wasn’t quite what I was getting at: it’s very common for (even otherwise reputable) people to “deflate” some price by the CPI and then say it’s the “real price”…NO!! to get the “real price” you adjust by changes in incomes, not prices (the logical and absurd result of this practice is that if you adjust ALL prices that way, you’ll find that prices – on average – never change).

Of course adjusting prices by the CPI might have some value in showing something – namely whether/not the item in question is rising, or even falling, in cost more/less than other items – but it doesn’t show the “real ” price….you need income data for that.

If you refuse to accept the CPI as an accurate estimate of the inflation rate, you have several other statistics from which to choose:

1. The spread between Treasury inflation-adjusted bonds and unprotected bonds is less than 2%, which implies that investors have the same expectations;

2. The Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland surveys producers and those surveyed, on average, expect inflation over the next ten years to average 2% per year;

3. MIT scientists run the Billion Prices Project, where they track the price trends of goods for sale online, and they also see annual inflation at about 2% per year.

Many of the items of which another anon refers are either driven by local market conditions – such as housing costs – or are a small fraction of the ‘average’ household’s spending. I agree if a household lives in SF and wants to send their kids to college next year and also need to pay for lifesaving drugs that they will certainly pay much more than in the past, but for the vast majority of households that situation is not a current concern.

This is a good discussion rarely found elsewhere in comment sections.