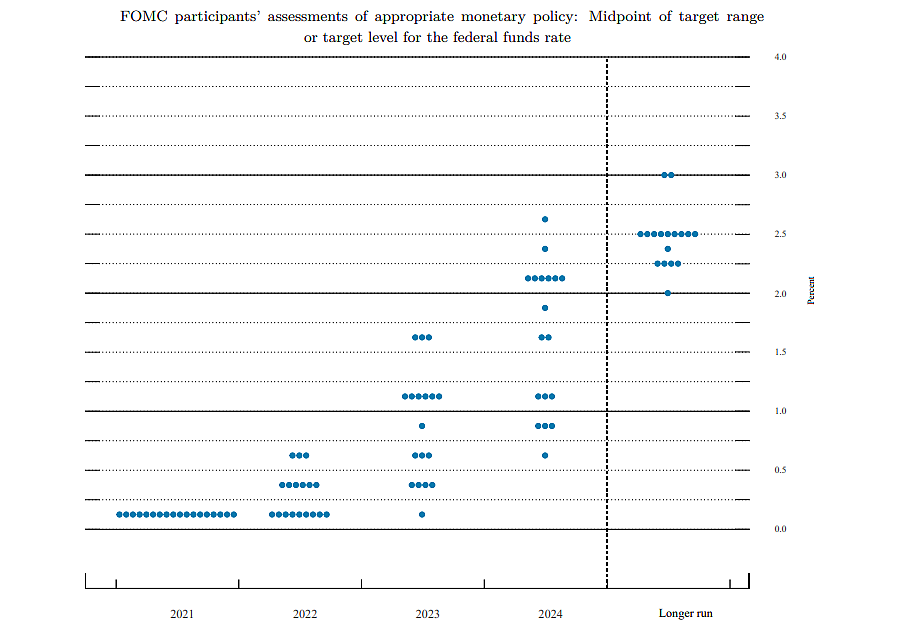

Having cited an ongoing public health crisis (i.e., the pandemic) that “will continue to weigh on economic activity, employment, and inflation in the near term, and poses considerable risks to the economic outlook” at the end of last year, the dot plot of Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) participant’s judgment of the appropriate target for the federal funds rate at the time had suggested that the Federal Reserve would likely wait until 2023 before instituting a rate hike.

But based on the latest dot plot, which was just released, FOMC members are now evenly split on whether or not rates should be raised next year, with the majority of members anticipating at least one additional hike, if not two, in 2023.

I wonder what the expectations for rate increases were amongst Japanese regulators in 1999. I seem to recall their regulators predicted an exit from the Zero-interest-rate policy by August 2000. I also seem to recall that their actual Bank of Japan discount rate has been zero, or less, with very few exceptions, continuously since late 1999 to today.

Sometimes what regulators say they want is not what comes to pass.

Japan is in an entirely different situation because their debt is held almost entirely domestically, as opposed to US. Much of their debt is used to finance domestic infrastructure which is not needed, only to provide jobs. To be sure, America certainly does not want to become the next Japan, but in the end the circumstances are vastly different, as Japan is experiencing an population decline and decrease in domestic demand whereas America is experiencing an extended postponement of fiscal responsibility and political accountability. One day soon the piper will come.

Sure, but probably not during your lifetime. The piper coming to be paid, that is.

Your second-to-last sentence should have ended with “…but in the end the circumstances are vastly different, as Japan is experiencing a population decline and decrease in domestic demand whereas America is experiencing at worst a leveling off in population and domestic demand because quite unlike Japan, the U.S. is the recipient of large net flows of international immigration”.

Someone please explain, to me, how the amount of U.S. debt held internationally is a structural feature of the U.S. trade deficit with the rest of the world. I dunno.

When interest rates increase the price of existing debt goes down. My understanding is that while a good chunk of Japan’s debt is held by the BOJ, seniors and families hold a lot of that debt as well. Pushing up rates and thus crashing the value of bonds that older people are holding for retirement is a very unpopular move to make. Between that and de-capitalizing your central bank makes raising rates a dicey proposition.

UPDATE: Prepare for Multiple Rate Hikes in 2022