Having hit a downwardly revised record of 555,000 in September, the number of people living in the city of San Francisco with a job slipped by 1,800 in October to 553,200. But with the labor force having dropped by 3,300 to 568,500, the unemployment rate actually dropped to 2.7 percent.

As such, there are now 87,700 more people living in San Francisco with paychecks than there were at the end of 2000, an increase of 116,500 since January of 2010 and 6,600 more than at the same time last year.

Keep in mind that employment in San Francisco typically ticks up, not down, in October. And the year-over-year gain last month was 50 percent lower than at the same time last year (13,100) and roughly a third the year-over-year gain recorded in October 2015 (18,500).

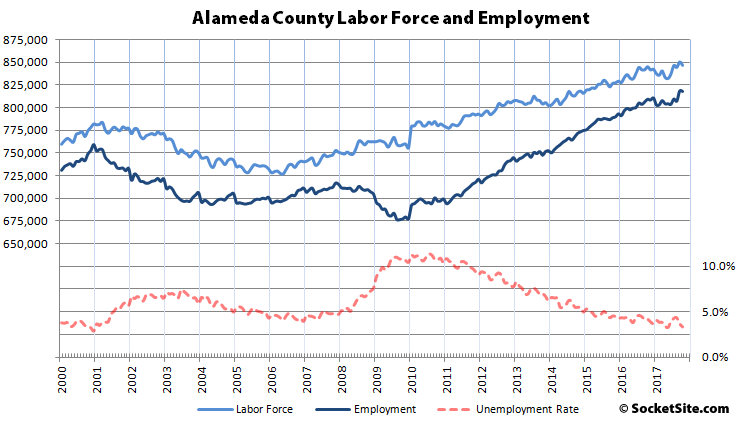

In Alameda County, which includes Oakland, employment slipped from a record 818,600 to 818,000 in October but remains 8,700 higher versus the same time last year and there are still 126,000 more people living in the Alameda County with paychecks since the beginning of 2010 and the unemployment dropped to 3.4 percent as the labor force fell from 850,200 to 846,600.

And across the greater East Bay, while employment slipped by a nominal 800 to 1,360,500, a decrease in the labor force dropped the unemployment rate to 3.4 percent.

Up north, the number of employed increased by 700 to 140,300 in Marin County, which is now within 600 of the record 140,900 set in December of 2000, and the unemployment rate dropped to 2.6 percent.

And down in the valley, while the unemployment rate in San Mateo County dropped from a downwardly revised 2.7 to 2.5 percent, it was driven by a decrease in the labor force and the number of employed residents actually slipped by 1,200 to 444,600 while employment in Santa Clara County inched up by 600 to a record 1,005,900 and the unemployment rate dropped to 3.0 percent.

Am I reading this right that in all of San Francisco there are only 15,300 unemployed people?

(At least according to these statistics)

Out of the 568,500 people considered to be part of San Francisco’s labor force (i.e., those working or actively seeking employment), 15,300 don’t have a job/paycheck.

That doesn’t include those who are retired, unable to work or have given up trying to find a job.

Not stating this as a fact, but as I’ve said before I’m going to conjecture that we are going to see a decrease in the relevance of unemployment as a stat due to the rise of gig jobs.

In the past, there were many reasons that people would not choose to be underemployed in a lower paying job vs being unemployed (i.e. not working and looking). Looking for a job is a full time job and working at a full time job makes it difficult to interview/network elsewhere. They didn’t want to show a downward trend on their salary history. Time and cost of training up/on-boarding for either the employee or the employer (which made them reluctant to hire overqualified people who were likely to only stay a short time).

Gig work removes most of these barriers and anecdotally, many people partake in the gig economy when they are without more permanent employment.

Uh huh. About 85 percent of gig workers make less than $500 a month, so unless you have property that you’re renting out on sites like AirBnB it’s highly likely that a gig job is going to be “a lower paying job” than more permanent employment.

Of course gig jobs offer freedom, but that utility to the worker is pretty much priced into their wages.

My point wasn’t to make a value judgement about if these gig jobs are good or bad for workers. Just that people taking them seems much more common than in the past. People who would never have taken a fast food job in the past will drive uber or the like without a second thought.

Your link states that: “About a quarter of all Americans participate in the sharing economy, according to Pew.” and deep linking into the Pew report reveals that 32% of those gig workers self-report not being otherwise employed. So I think that shows that this is a change of some significance. The Pew report also states that the BLS is looking into these “contingent and alternative work arrangements”, so at some point going forward I’m sure we’ll have a more accurate picture of how gig work is impacting the labor market.

It would make a big difference to housing developers if there is more precise data regarding the number of gig workers as opposed to the full-time or even part-time employed. Gig workers are unlikely able to afford new apartments or buy new condos. Though the overall picture shows low unemployment, it is more meaningful to see the type of employment involved.

Residential leasing agents I know won’t even count gig jobs as employment in evaluating prospective tenants.

“The Bureau of Labor Statistics has been tracking “contingent and alternative work arrangements” for a number of years (most recently in 2005) and will be including supplementary questions designed to capture technology-enabled “gig work” in its May 2017 survey.”

12+ years from tracking a trend to including supplementary questions on a survey. Government statisticians surely don’t move fast, but I do think that eventually there will be better data about this.

I wonder if that 85% number is the same in the Bay Area.

Gig jobs aren’t going to cut it in the most expensive city in America. Rideshare drivers come in from many hours away.

This is probably mostly due to people who lose (or quit) their jobs leaving SF immediately due to the cost of living, and not hanging around long enough to be counted as unemployed.

The other factor could be spouses quitting their job to take care of the kids, of which I know quite a few couples. Because childcare has become so expensive, it’s more cost effective to quit your job if it only pays a middle class salary, and if your spouse is making silly tech money on the other hand.