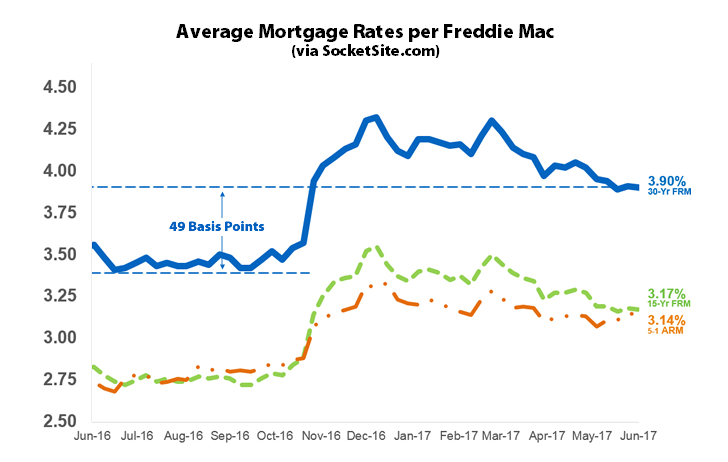

With the probability of the Fed’s rate hike last week already priced in, the average rate for a benchmark 30-year mortgage barely moved over the past seven days, dropping one (1) basis point to an average rate of 3.90 percent and to within one (1) basis point of the lowest average rate this year.

At the same time, the benchmark rate remains 34 basis points above the 3.56 percent rate in place at the same time last year and 49 basis points above last year’s 3.41 percent low, according to Freddie Mac’s Primary Mortgage Market Survey data.

And according to an analysis of the futures market, the probability of the Fed effecting another rate hike by the end of the year is hovering around 50 percent with more certainty of another hike in March.

Mortgage rates generally follow the 10-year Treasury rate curve, not the overnight rates set by the Fed. The 10-year T rate is little changed in June (although very slightly lower). That means the “yield curve” (chart of rates for various durations of Treasury debt) is flattening with longer rates, set by the markets, not rising as the Fed hikes shorter rates. This puts a limit on future Fed hikes because they do not want to push overnight rates above longer term rates, a formula for recession.

And to take it one step further, a flatter yield curve generally means a slowing economy, the curve is starting to look a lot like 2007.

In the time before the 2008 financial crisis, it was true that the Fed only set short term interest rate while the market set longer term rates. But even with short term rates near or at zero some policy makers felt that more monetary stimulus was needed so the Fed, ECB and other central banks engaged in “Quantitative Easing” in order to directly reduce longer term bond rates in general and specifically mortgage bond rates. This was done by having central banks buy up bonds in order to drive down yields. The Fed alone bought up $4.5 Trillion worth of bonds, some Treasuries some MBS, in order to push down rates. The ECB is still actively buying bonds and now even buys up corporate bonds.

Hard to know what the Fed or other central banks will do, but were they to desire to raise rates across the yield curve they could merely sell some of their holdings with longer durations thus pushing up yields at that point in the curve.

Yes, you are right that Fed actions can influence longer rates through their buying and potential selling of bonds, but they do not directly set longer rates the way they do the overnight Fed Funds rate and they have so far shown no inclination to do other than not replace a small portion of their large (about $4 trillion) bond holdings as those mature (that is, they have said nothing to indicate they contemplete actual bond selling). The effect of their throttling back on “quantitative easing” in this way so far has been nearly imperceptible; that is their actions that should raise rates by reducing demand for bonds have not ctually done so.

Well said BTinSF. Add in international bond rates for 10 years and other duration that are generally lower than US treasury bond rates and we are very unlikely to see much upward movement in mortgage rates.

If “risk free” US Treasury is safer and better value than Japanese, German, British government bond, there will be buying pressure thus pushing down the rate for the asset. And thus keeping our mortgage rates low.