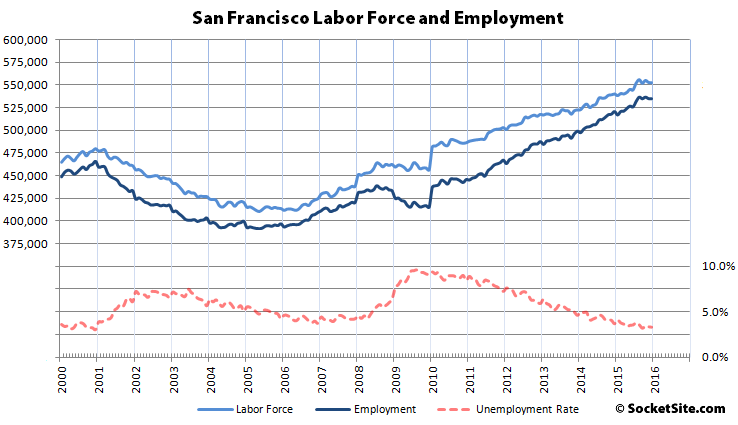

For the second month in a row, the number of people living in San Francisco with a job slipped. And while it was a nominal drop of a hundred, from 534,700 to 534,600, it was the first December without a gain since 2009 and versus an average December increase of 2,920 over the past six years.

But with the labor force having slipped by 400, and the number of unemployed by 200, the unemployment rate in the city remained at 3.3 percent, the second lowest unemployment rate in San Francisco since December 2000.

There are now 69,100 more people living in San Francisco with paychecks than there were at the height of the dot-com peak in 2000, up by 14,100 over the past year and an increase of 97,900 since January of 2010, which is a 22 percent increase in employment in just under six years according to data provided by California’s Employment Development Department. But the growth rate has been slipping for five months straight.

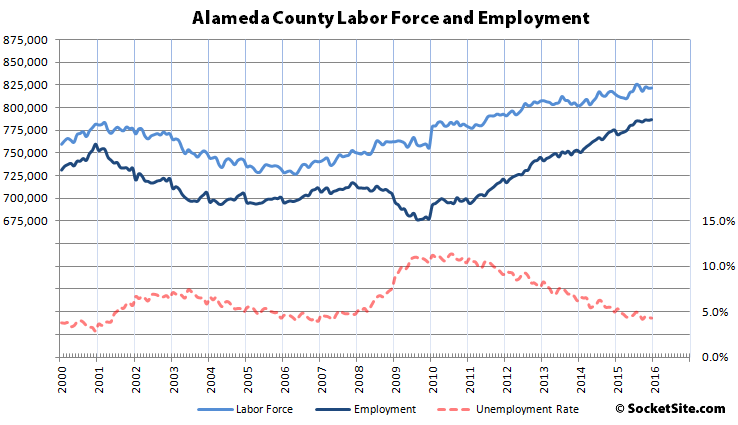

At the same time, East Bay employment ticked up by 1,000 in December to 1,310,900, with employment in Alameda County, which includes Oakland, accounting for 80 percent of the gain and now measuring 786,200, an increase of 11,300 over the past year.

And with the labor force in Alameda County having increased by 200 last month to 821,900, the County’s unemployment rate has dropped to 4.3 percent, down from a revised 4.4 percent in November and versus 5.0 percent in December 2014.

Could be that SF is fully occupied now and people are moving to Oakland.

However, more likely that the job growth has slowed in all the bay area. Is the economy slowing down?

Why would you think the latter?

Yes, and yes. SF has truly hit the affordability ceiling. At the same time, full employment is one of the best historical predictors of a coming recession, US jobless claims under 300,000 usually foreshadow a recession coming in 1-2 years. This being a function of failed Fed policy, which despite its intent, favors wealth over growth.

Why, yes, since SF was down by 400 and AlCo was up by 200 it’s possible half of them did just that (the other 200 are probably still stuck in traffic)

Would someone kindly explain the difference between labor force and employment?

Google is your friend…but I’ll help. Labor Force: every person of working age who is employed, or actively looking for work. Employment…um…that would be everyone who has a job.

I think he/she may be confused by SS’s continued insistence in labeling these charts as “SF (or wherever) Employment” as if they showed where people are working, when in fact they show where people who have – or don’t have – jobs live.

If I live in SF, but commute to Cupertino/Mtn view, am I considered both employed and part of SF’s labor force?

Yes.

Yes, but you do not count as a “job” in San Francisco. So when you see reports of SF having 650,000 jobs, your job is not one of them. You are just an employed resident. While they both matter a lot for housing prices, policy folks are usually looking more at how many jobs there are in the City as a better indicator of the direct correlation to local housing prices and how much housing needs to be produced. However, with the job market being very regional and people obviously more and more preferring to live in SF even if they work elsewhere, the number of employed residents is becoming more and more relevant (ie overall bay area job growth, not just SF job growth). It’s pretty notable that SF had very close to the same amount of jobs in 2000 at the height of the dot com boom but 100,000 fewer employed residents. That means that either more SF jobs are held by SF residents (my info says that this actually hasn’t changed much, still around 50-55% of SF jobs), or a higher proportion of housing units in SF are occupied by people who work elsewhere (I haven’t seen data, but I put my money on that one).

We’ve covered this in the past, but the number that really counts with respect to housing prices is local employment, not jobs. To understand why, look to your own words: “a higher proportion of housing units in SF are occupied by people who work elsewhere.”

Policy folks look at job forecasts in an attempt to estimate future employment. We track and report the actual number and trends which drive the market.

Not exactly rocket science, but I find [the SF] chart very interesting when comparing it to the first release of the iPhone (Summer 2007). I understand that there are a large number of private companies way overvalued, burning through cash, with VC investing slowing down. I also understand that SF’s economy is not just based on s/w and apps. That being said, we’re just BEGINNING to use our personal mobile devices to a great potential. It’ll be interesting to see if this talk of a “bubble” is real or not!

This. I said something to this effect in some SS comment or other six months back. I think people still don’t understand just how real and sweeping a paradigm shift the “App economy” is. It has become the Ford / GM / Chrysler of the 21st century. Totally different product line and economics, but similar in scale and socioeconomic impact.

Those billion-plus smartphones are here to stay and they’re only going to get smarter.

Have you seen any data on the income/profit distribution for the app economy?

Most apps net peanuts with a very small number of apps getting the majority of the pie.

Now the app stores that get a 30% cut while they enhance the lock in effect for their platform with each app purchase. Now that’s a good paradigm.

The vast majority of apps are useless. You can’t even parody them any more (who can live without doggie game consoles?). Even if your premise about the “App economy” were true, cost-cutting is coming to the surviving companies. People who actually know how to run a business for profit will be in charge, instead of koder kiddies who know nothing about business, other than blowing throwing through angel investor capital at breakneck speed.

The biggest costs for the coder companies are labor and commercial rent. Labor costs are so high partly because of the high cost of housing. To cut costs, many of the surviving companies will have to move to areas with cheaper commercial and residential rent. Unlike the auto industry, which had specific reasons to be Great Lakes region, there really is no need for the coder sector to be in the Bay Area. Sure, Stanford and Berkeley are great schools, but there are great schools all over the place. You don’t need to go to Stanford to learn node.js.

Programs are now being created that will do much of the coding that the kiddies now do. You only need a handful of people to maintain programs that can do the work of dozens of kiddies. There’s nothing done in the Bay Area coder sector that can’t be done better and more cheaply abroad, or that soon will be done by robots. If the coder sector is going to thrive and compete with India and other countries, it will have to move to cheaper areas.

This sounds pretty similar to stuff being said for 40 years. Why hasn’t it happened yet?

You have good things to say. So why the reaches, always? You don’t do yourself any favors. Here you’ve taken the reductio ad absurdum routine regarding apps, as if the whole industry is apps, and ran with it. Then you’ve gone with the trope that is “Everybody is gonna move to a server farm out in Ames, Iowa,” and ran with that too. Why? You probably already know the answers to these things, and the answers are true.

I think you’re distorting my statements. Maybe I’m can be a little over the top. I also have repeatedly said that there are legitimate companies that will survive, but that they will have to downsize. How much downsizing? I don’t know. But the evidence shows that we are entering a deflationary cycle (brought on by the gradual easing up of thirty years of historic loose monetary policy designed to prop up stocks and housing, and I wouldn’t be shocked to see a QE4 in the future to try to keep the party going), and if this is true, no one will be unscathed, and that includes the hallowed Bay Area tech sector. Of more concern to this blog’s readers, housing will also be affected by this deflationary cycle. How much? I don’t know. All I can do is see the larger trend, but I can’t predict how big the cuts will be.

Ah, there’s the hard money two beers that we all know and love. Austrians never had such great friends on the “left”.

anona-

First, apart from you, me, and Tommy, I doubt if few else here have ever even heard of Austrian economics.

Second, you sound like a crank. 99% of economists would say we’ve gone through seven years of loose monetary policy. For you to claim that we’ve gone through seven years of tight money makes you sound like someone from the Flat Earth Society. “Screw the evidence and the experts: what I know is right!”

Maybe you conflate monetary policy with fiscal policy? In that case, I would agree that fiscal policy for the last seven years has been too tight (and that’s a political decision made to bail out Wall St with monetary stimulus instead of bailing out Main St with fiscal stimulus). Hell, even your cherished new-Keynesian liberal monetarist Friedmanite Christina Romer recommended a fiscal stimulus much larger than the one Obama asked for.

If you are conflating monetary and fiscal policy, you have no business commenting on economics. The concept that all economic problems can be handled with mere adjusting of interest rates (past the zero-bound even, into negativeland) is bonkers, but Uncle Miltie Friedman said it, you believe, and that settles it. Parts of Europe are going negative now; let’s see how that works out! Of course, when it fails, you’ll say “it wasn’t negative enough!” Throw the witch in the water. If she floats, she’s a witch, but if she sinks, she wasn’t one. You get to have it both ways!

That you confuse Austrian economics with post-Keynesian economics is another sign that your knowledge of economics stops with the New Keynesian Friedmanites. The boom-and-bust financialized bubble economy created in their image has discredited their dead-end branch of econ.

Post-Keynsian econ disproves the Austrian bunkum concerning hard momey. That you can’t tell the difference is another sign that you have little understanding of economics past neo-classical econ textbooks from 1990.

I’m sorry if the econ you learned in college has been proven faulty. It’s hard to face it when one’s ideology proves to be bogus. Cognitive dissonance is a b*tch.

It hasn’t happened because it isn’t true. Sales and marketing costs are higher than R&D for the software companies where most coders work in the bay area. For example, Salesforce R&D is under 20% of revenue, while marketing and sales are more than 50%. Similarly, R&D cost are less than 20% of revenue and lower than S&M at Google, Microsoft, Oracle, etc. You will see those kind of percentages for just about any sw company beyond the startup phase, which is where most people work.

One of the more troubling things about Twitter is that their R&D costs are such a big percentage of revenue, ~40%. Unless they roughly double revenue without increasing R&D, they will have trouble being profitable and may not survive as an independent company once their IPO cash burns out.

There are always tiny “coder companies”/startups that don’t make a profit and disappear because of lack of sales not the high cost of housing. For the bulk of bay area software companies, even if the housing costs of their employees were cut in half and the companies got to keep all the savings, that would only be a few percent of their costs. One bad decision by the VP of marketing wastes more than that.

And there are compelling reasons for a large “coder sector” to be in the Bay Area. A concentration of top talent makes for higher productivity. Just ask the founders of hundreds of companies including Netscape and Facebook that moved to the bay area. Not an accident. Besides, they need the eggs.

Another problem is that you’re ignoring the societal shift that’s taken place. Young techies want to live here, not in Des Moines (at least in aggregate).

And if you honestly believe that robots will soon be able to code like people do, well, good luck.

“This sounds pretty similar to stuff being said for 40 years. Why hasn’t it happened yet?” “And if you honestly believe that robots will soon be able to code like people do, well, good luck.”

This is exactly what has been happening for a long time now.

No-one does IC design by hand cutting Rubylith anymore and not much software is hand coded assembly.

But the key question is who builds the “robots” that do the work that used to be done by hand. And the answer is very highly skilled engineers, many of whom reside around the bay area.

The medium skill jobs that get automated aren’t really going to India, they mostly just disappear. Why have a person do what a computer can do better.

The phone platforms provide great tools that make it so that nearly anyone can build an app. But if nearly anyone can build a product to compete with yours, what do you think that does to your profit margin? Of course the companies providing the mobile phone platforms will keep hiring very highly skilled individuals who can build the next generation of tools…

The bay area having a small set of top talent is nothing new. As Jake points out, the ability of companies with no profits and no prospects of profit to bring high returns for investors is what’s new. Because if profitless companies can bring in high returns for investors, why not create profitless companies? And while there might be a supply constraint on good ideas and the ability to run a company well, what’s the supply constraint on creating a money losing company? And with all these companies being created, what does that artificially increased demand do to mid skill tech compensation?

As another poster pointed out, 2 beers has some good points, but takes them too far. There’s a wide space between the viewpoint that robots will make the bay area the next Detroit and the viewpoint that profits are obsolete and multi-billion dollar valuations can be sprinkled about like candy.

“Those billion-plus smartphones are here to stay and they’re only going to get smarter.”

Can Apple escape phone fatigue?

“It will be tough for Apple to top last year’s results, when the tech giant posted the highest profit of any public company ever,”

Just step back for a moment though and ponder the “problem” of being able to top the record of the most quarterly profit for any company ever and the problem of companies that have had no profits ever.

I was responding to to the claims that smart phones and apps are the new economy and big enough to smooth over the unicornalpyse. The linked article says that Apple will have difficulties maintaining its epic growth. That means declining growth. I’m not saying Apple is going to fail, only that it’s unrealistic to expect it to save the Bay Area housing economy.

Sure, but your other statements have implied that we’re “already in a depression, some say”. That’s generally defined as a two year or longer recession or a 10% decline in real gdp. You’re arguing that we’re facing economic apocalypse, not that growth will slow.

I’m saying that at best, growth will slow. I’m also saying that what looks on paper as a booming economy due to the trillions of dollars the Fed gave Wall St actually feels more like a severe recession for tens of millions of Americans.

That’s very, very different from a depression.

I never said the aggregate economy is in a depression, but thanks for playing. Get back to me when you’ve learned 1)the difference between post-Keynesian and Austrian economics, and 2) why New Keynesian econ has failed.

btw, you keep reminding me of the Dutch term, “mierenneuker.”

lol, I absolutely agree that New Keynesianism has failed, I thought we went over that? And you absolutely said exactly that we’re “already in a depression, some say”.

It is very good to see that Bernie Sanders has now come out in favor of packing the Fed with more doves, and hopefully easing the insanely tight money that we’ve had for the past decade, at least until we get to sub-4% unemployment.

Your hero Romer is considered a New Keynesian. Your other market monetarist heroes are just linguistic tweaks on Milton Friedman. The end result is the same: the Fed just pumps more money into banks that never gets to the working people who need it, and instead creates massive asset bubbles like the one we’re now in.

“insanely tight money that we’ve had for the past decade”

Dude, you’re embarrassing yourself.

We get it, you view the totality of monetary policy stance to be the nominal interest rate. So you see super tight money in the 70s and crazy loose money in the only two deflationary times of the past century. Seems disconnected from the real world, but ok.

Romer isn’t much of a New Kenyesian any more. She has distanced herself from that naming convention several times over the last five years, as NK beliefs have been more and more discredited.

I’m still clear on what solutions you offer, other than tighter money now!

Apparently you deny the existence of QE1/2/3, the largest monetary stimulus in the history of mankind, trillions of dollars poured directly into the Wall St banks you worship and/or work for.

Apparently you’ve also never heard of fiscal stimulus, or if you have, you think it’s the same thing as monetary stimulus.

You’re possibly one of ten people on the planet who think ZIRP and QE1/2/3 was “insanely tight money.” Frankly, you’re a crank, and I regret the time I’ve wasted trying to engage you in rational discussion.

Get back to me when you’ve learned what the purpose and function of the Fed is, what the limits of monetary stimulus are, and “why fiscal stimulus” are the awful words that must not be spoken among you and your banker overlords.

One of ten people on the planet. Ok. Perhaps you never read the New York Times. Peace.

I don’t know why you keep saying that I oppose fiscal stimulus. I supported it in 2008-09, and I’d support it at any time where monetary easing alone is not enough (so perhaps now). That really has little bearing on whether I also think that monetary policy is too tight. Fiscal policy is simply much harder politically, so I’d prefer to you know, try the easier one as well.

You’re right though, let’s continue to tighten monetary policy even more. I’m sure that the Republican House will get on the fiscal stimulus bandwagon any day now.

If you are looking for what turned the inflection point for SF tech in 2004-2007, it would be web 2.0/social, followed by video and ad tech, with a good dose of agile/cloud lower cost to build and operate. iPhone sales didn’t really explode until 2008Q4. The social network frenzy had already coughed-up a $850 million hairball for Bebo by then.

Smartphone/mobile, the faster cellular data nets, and the big data on-net clouds that offload the toy in your pocket are really the third wave in creating a bigger market for personal/individualized computing: PC, Internet, mobile. Each a much bigger market with lower cost to reach. Checkout wish.com for an SF app that exploits mobile.

Do you have a term for this third phase? I’ve been calling it AppNation 1.0 occasionally (and the Fisher Price Web when I get frustrated by how a web page renders thanks to Google’s mobile or die mandate).

Most people just call it “mobile”, but it also bleeds into the “internet of things”. It all comes from nano scale tech (processors, transducers(radio), sensors, motors, etc) enabling ubiquity: GHz for a buck, MHz for a penny. Most apps are just UI controllers layered on the real system code that runs the hw and the cloud-based analysis sw that grinds the data and tunes it for you or sells you (adverts) . Cloud/grid/cluster computing and connectivity are the necessary compliments to your smartphone. Try running your phone in ‘airplane’ mode for a week and see how valuable standalone apps are.

How about “mobile intertubez”? Sorry, just have to get that networking in there — packet switching finally beating all challengers.

Speaking of the cloud, I recently saw that Google announced they’ll be able to run your Android apps in the cloud instead of having to download them locally. We’ve basically gone full circle back to a mainframe computing model (with really smart “dumb” terminals and, look ma, no wires).

Yep. With a 3.3% unemployment, other cities would do anything to have our problems

Direct relationship between low interest rates, VC funding, and real estate prices.

A moving average representation of the data in that graph would make the correlation even more obvious.

That chart does not show interest rates. US interest rates were not correlated with bay area apt rent prices over the past 20 years. For example, the Fed Funds rate was 5-6% through the entire dotcom bubble and burst into the recession. Yet rents took a roller-coaster ride going up 50-100% over ~5 years and then collapsing back down. And US mortgage interest rates were higher during the dotcom boom than any time since, and the next mortgage interest rate peak was in 2007-2008 when rents were going up, but they’ve been low during the current rent runup. That means no direct correlation.

Also, your link charts the average size of a VC deal in the bay area, not the total amount of money the VCs invested. By ignoring the number of deals, it exaggerates the end-of-cycle investments, which tend to be larger as VCs pull back on making early round/seed bets and lean towards trying to save the bigger fish that they can’t pawnoff through a tightening IPO window. That’s what we’ve seen over the past year or so, and what we saw after the NASDAQ crashed in early 2000.

Even when you get past the dotcom bubble, the chart itself shows no correlation between VC deal size and apt rent during the decade plus of 2003-2013. It does show that during that period the deal size had little variation staying in the $7-10 million range, while rents went through another up-down-up ride. That means no direct correlation.

I’m fairly confident that if you computed the actual correlation coefficients between these quantities, you’d find a poor or low correlation. Notice how in the first boom it looks like the VC deal size leads the rent increase, while in the current boom it looks like it follows. Hmmm, stats don’t like correlations that switch signs, mega-inconsistencies don’t make for good theories. If you eyeball that chart and “see” a correlation, then you may as well give up substituting your pattern recognition skills for generally accepted stat calcs.

One major difference is that during the dot com bubble, it was public money not VC driving the over-valuations. Most of the current unicorns have not gone public, and part of that is a deliberate strategy, they know that if the public were to actually weigh in on their value it might expose them as donkeys with horns taped to their heads.

In SF the dotcom boom depended more on VC money than the current boom does. SF had some nice dotcom IPOs, but nothing like the valley. VCs have been putting a little less than $1B/month into SF during the current boom. SF Planning’s summary of the dotcom boom and early bust in SF (8 page pdf at namelink) is the most succinct summary of this period for this place that I know. Here’s a snippet:

“Between 1994 and 2000, San Francisco experienced a period of sustained growth and added over 86,000 jobs….In 1996, venture capital (VC) companies provided about $10 billion to Internet and other high-tech start-up companies in San Francisco. Funding continued at about that level until 1998, when the funding rose 20 percent to $12 billion, even though many of the companies were not generating any profit. The amount of venture capital funding continued to rise and many new high-tech companies started to grow very rapidly, hiring staff and leasing more office space. In 1999, VC funding rose to $40 billion. In 2000, the last year for which we have complete information, VC funding exceeded $50 billion for start-up companies in San Francisco. This funding allowed the expansion of the high-tech office space. The reported leasing activity increased from about 0.5 million square feet to 4.25 million square feet.”

Inflation adjusted, the current VC investment rate in SF is only ~75% of when Yahoo went public in 1996, which was about when things really got crazy in SF, and a mere 15-20% of when the party crashed in 2000.

BTW, one key to the easy run-ups in valuation both now and in the dotcom era is the potential of exit via IPO for money-losing companies. Before the dotcom era it was rare to go public without a few quarters of profit, but once wallstreet/pagemillroad learned how to sell momentum/topline instead of results/bottomline, why wait for or bother with profit.

It isn’t actually an Oakland chart, but an Alameda Cty one, of which Oakland is only about a fourth. And the charts aren’t where jobs are located, but where people who have jobs live …as in some of the numbers for AlCo work in SF, SM or SC counties (and vice-versa, though to a lesser degree).

These numbers are all just rounding errors on the data. The only possibly interesting fact is that the growth rate of employment has tapered off to essentially nothing, which may reflect the simple fact that there can only be so many warm bodies living and working in San Francisco, absent significant new construction to accommodate more people.

I think that’s probably the best explanation for this chart. SF’s population growth is pretty slow (what’s our yearly average for new units over the last 5 years? >5000 I bet) and we’re about maxing out how many people can be crammed into our existing housing. It’s reasonable to think that our overall workforce is going to effectively plateau

“Tim Cook: We’re Seeing ‘Extreme Conditions Unlike Anything We’ve Experienced Before’ in the Global Economy”

Strong Words.

Even a very big ship can be shaken by a large enough storm.

But when a storm is big enough to shake the largest boats, what does that do to the smaller boats? Especially to ones that are very poorly constructed?

Sounds like Tim Cook read the first letter. How soon they forget 2008-2009. Of course dealing with the global financial crisis and near depression of those days when you have a breakout product like the iPhone was then is unlike having to deal with the much less volatile current situation with a more of the same product line like Apple has now.

I look forward to Tim Cook’s reading of the second letter.